|

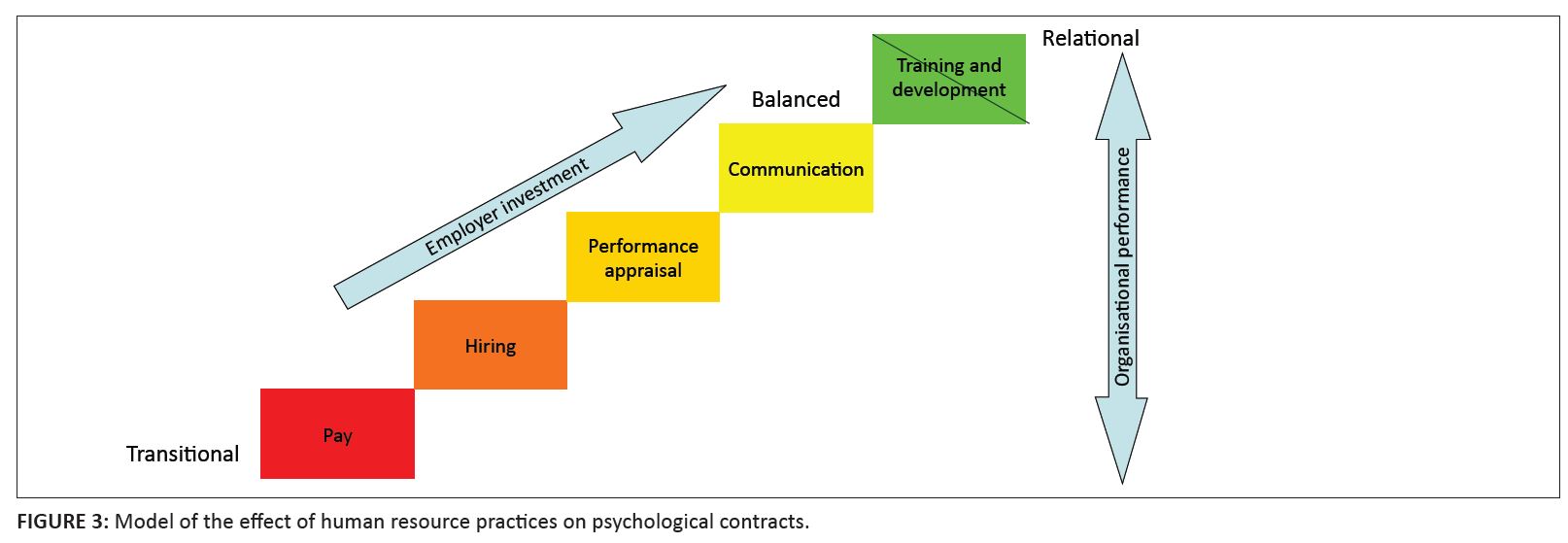

Orientation: Human resource practices influence the psychological contract between employee and employer and, ultimately, organisational performance. Research purpose: The objective of this study was to examine the effect of human resource practices on the types of psychological contracts in an iron ore mining company in South Africa empirically. Motivation for the study: Although there have been a number of conceptual studies on the effect of human resource practices on psychological contracts, there has been no effort to synthesise the links between these contracts and various human resource practices systematically. This study endeavoured to provide quantitative evidence to verify or refute conceptual studies on this relationship. Its findings could inform human resource strategies and, ultimately, the prioritisation of human resource practices to improve the cost-effective allocation of resources. Research design, approach and method: The researchers administered two questionnaires. These were Rousseau’s Psychological Contract Inventory (2000) and the Human Resource Practices Scale of Geringer, Colette and Milliman (2002). The researchers conducted the study with 936 knowledge workers at an iron ore mining company in South Africa. They achieved a 32% response rate. Main findings: The findings showed that most participants have relational contracts with the organisation. Another 22% have balanced contracts, 8% have transitional contracts whilst only 1% have transactional contracts. The study suggests that there are relationships between these psychological contracts and specific human resource practices. The study found that training and development was the most important human resource practice for developing relational and balanced contracts. Employees thought that they contributed more than their employer did to the relationship. The researchers developed a model to illustrate the influence of the various human resource practices on psychological contracts. Practical/managerial implications: The influence of human resource practices on relational contracts could assist organisations to invest in human resource practices. During recessions, organisations tend to reduce expenditure on human resource practices, especially training and development. The findings of this study, about the relationship between training and development and relational contracts, highlight the negative effect that this trend could have on psychological contracts, individual and organisational behaviour and, ultimately, organisational performance. Contribution/value-add: Based on this empirical study, the researchers proposed a conceptual model to illustrate the relationship between different psychological contracts and specific human resource practices, like training and development, which had the strongest relationships with relational contracts.

Numerous studies emphasise the importance of psychological contracts between employer and employee (Freese & Schalk, 2008; Rousseau, 2004; Rousseau & Wade-Benzoni, 1994; Wöcke & Sutherland, 2008). Organisations invest in human resource practices, like remuneration, training and development, to improve these relations (Martin, Staines & Pate, 1998; Sims, 1994). Although research has shown that human resource practices influence psychological contracts (Guzzo & Noonan, 1994; Martin et al., 1998; Sims, 1994), it is crucial to synthesise the links between specific human resource practices and psychological contracts systematically to inform these investments. Therefore, the researchers had to gather descriptive data on the relationship between human resource practices and psychological contracts. Psychological contracts refer to beliefs people hold about promises others make to them and which they accept and rely on (Rousseau, 1995). In organisations, these contracts include employers’ and employees’ expectations of each another (Rousseau, 2004; Rousseau & Wade-Benzoni, 1994). They give an insight into difficulties about employment relationships and the implications of these difficulties on individual and organisational behaviour (Aggarwal & Bhargava, 2008). The researchers conducted the study on knowledge workers at an iron ore mining company in South Africa. One of the characteristics of knowledge workers is their high turnover level, with the consequent high costs to the organisations that employ them. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the psychological contracts that knowledge workers have with their organisations. Particularly in times of recession, cost-effective spending on human resource practices is essential. Through determining which human resource practices play significant roles in building psychological contracts with knowledge workers, this study could assist to prioritise the allocations of resources to these practices. Against this background, the purpose of this research was to answer the research question: ‘what types of psychological contracts do organisations have with knowledge workers and what is the effect of human resource practices on these contracts?’ More specifically, the objective of this study was to examine the relationships between these different types of psychological contracts and human resource practices empirically. The article has four parts. Firstly, it reviews the literature relevant to psychological contracts and human resource practices. Secondly, it presents the research design and discusses techniques of data analysis. Thirdly, it presents summarised findings. The article concludes with a discussion of the implications for managing human resources and suggestions for future research.

This review of the relevant literature explores psychological contracts, human resource practices and their relationships.

Psychological contracts

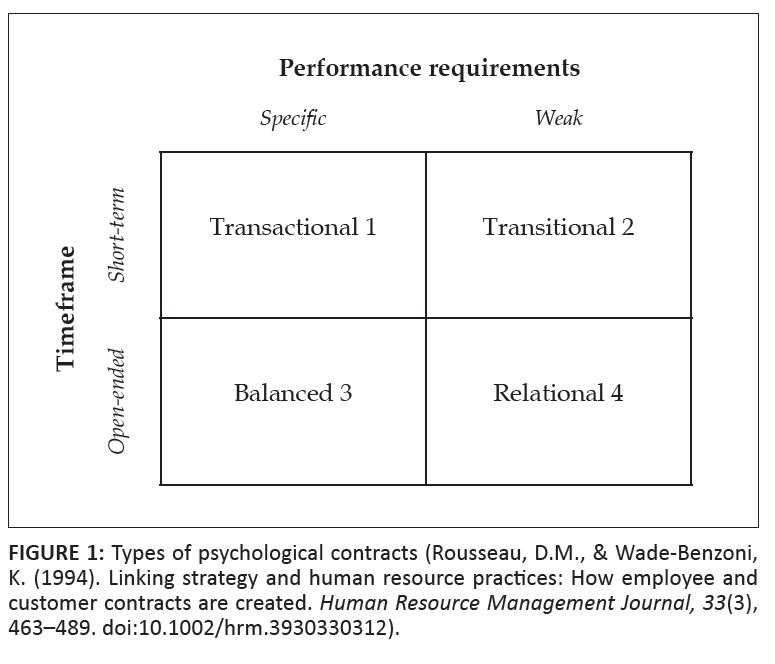

Secondary evidence on psychological contracts reveals critical relationships between employers and employees to ensure productivity, continued innovation and creativity (Coyle-Shapiro & Kessler, 2000; Flood, Turner, Ramamoorthy & Pearson, 2001; Maguire, 2002). Historically, employers expected employees to work hard to meet the demands of their managers. In return, employers would provide job opportunities with guaranteed advancement and lifetime employment (De Meuse, Bergmann & Lester, 2001; Strong, 2003). However, this traditional structure of employee-employer relationships, based on an edifice of trust, loyalty, commitment and long-term relationships, has changed (Arnold, 1996; Herriot, Manning & Kidd, 1997). The demands of globalisation, continual technological developments and the diversity of market requirements have forced employment relationships to change (Strong, 2003). As the pressure on organisations to become more flexible, adaptable and efficient increases, they may engage in strategies that alter employees’ perceptions of the employment exchange (De Meuse et al., 2001). The dynamic nature of contemporary employment relations has led to an emphasis on two particular contract terms: the timeframes and performance requirements of the contracts (Rousseau & Wade-Benzoni, 1994). Two major types of contracts are common in the workplace. They anchor two ends of what have been described as contractual continuum-transactional and relational contracts. When one arranges these two contract features in a two-by-two framework (see Figure 1), one can identify four types of contracts: transactional (1), transitional (2), balanced (3) and relational (4). Rousseau (2000) defines the transactional contract (1 in Figure 1) as an employment arrangement with a short term or limited duration. It focuses primarily on: • economic exchanges

• specific, narrow duties

• limited worker involvement or development in the organisation. The employer offers employment for a specific or limited time and is not bound to future commitments. Freese and Schalk (2008) also emphasise the transactional features of psychological contracts. They warn that their features resemble traditional labour contracts more closely than psychological contracts do as mental models of employee attitudes and behaviour. Rousseau (1995, 2004) emphasises another kind of short-term contract in which performance requirements are weak. She warns that the transitional contract (2 in Figure 1) is not really a psychological contract but a cognitive state that reflects the consequences of organisational change and transitions that are at odds with an earlier employment contract. It is a breakdown in contracts. It lacks commitment about future employment and has few or no explicit performance demands or contingencies. It is a state one finds in organisations that are closing down. The literature defines balanced contracts (3 in Figure 1) as specific and open-ended employment arrangements conditioned in terms of the economic success of organisations (Wöcke & Sutherland, 2008). Workers can develop their careers and both workers and organisations contribute greatly to each other’s learning and development. Performance and contributions to the organisations’ competitive advantage, particularly in the face of changing demands that market pressure causes, determine the rewards to workers. In this sense, they are more conditions than psychological contracts. The relational contract (4 in Figure 1) is an open-ended, less specific or weak agreement that establishes and maintains a relationship based on emotional involvement and financial reward (Robinson & Rousseau, 1994). The employer commits to stable wages and long-term employment. The employee is obliged to support the organisation and to be loyal and committed to the organisation’s needs and interests. Rousseau (2000) developed an instrument called the Psychological Contract Inventory (PCI) to measure the features of psychological contracts (Freese & Schalk, 2008). It is based on the conceptual framework shown earlier and is grounded in organisational theory and research. Although there are other views about the different types of psychological contracts that co-exist in employment relationships (Isaksson, 2005), this study used Rousseau’s (2000) method of assessing one type of psychological contract in each employment relationship. Balanced contracts are types of psychological contracts based on the economic success of organisations and employees’ opportunities to develop their careers (Rousseau & Wade-Benzoni, 1994). However, this study sees them as psychological contracts based on the theoretical framework of Rousseau and Wade-Benzoni (1994) for the four types of psychological contracts. Transactional and relational contracts can exist in one employment relationship. An example is the high-performance work team (Rousseau, 2000). The focus of this study was the relationship between the different types of psychological contracts and human resource practices. Therefore, Rousseau’s (2000) frame of reference provided a useful method of analysis. Human resource practices, like recruitment, training, development and remuneration, determine the state of these psychological contracts. The next section discusses these practices.

|

FIGURE 1: Types of psychological contracts (Rousseau, D.M., & Wade-Benzoni,

K. (1994). Linking strategy and human resource practices: How employee and customer contracts are created. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(3), 463–489. doi:10.1002/hrm.3930330312).

|

|

Human resource practices

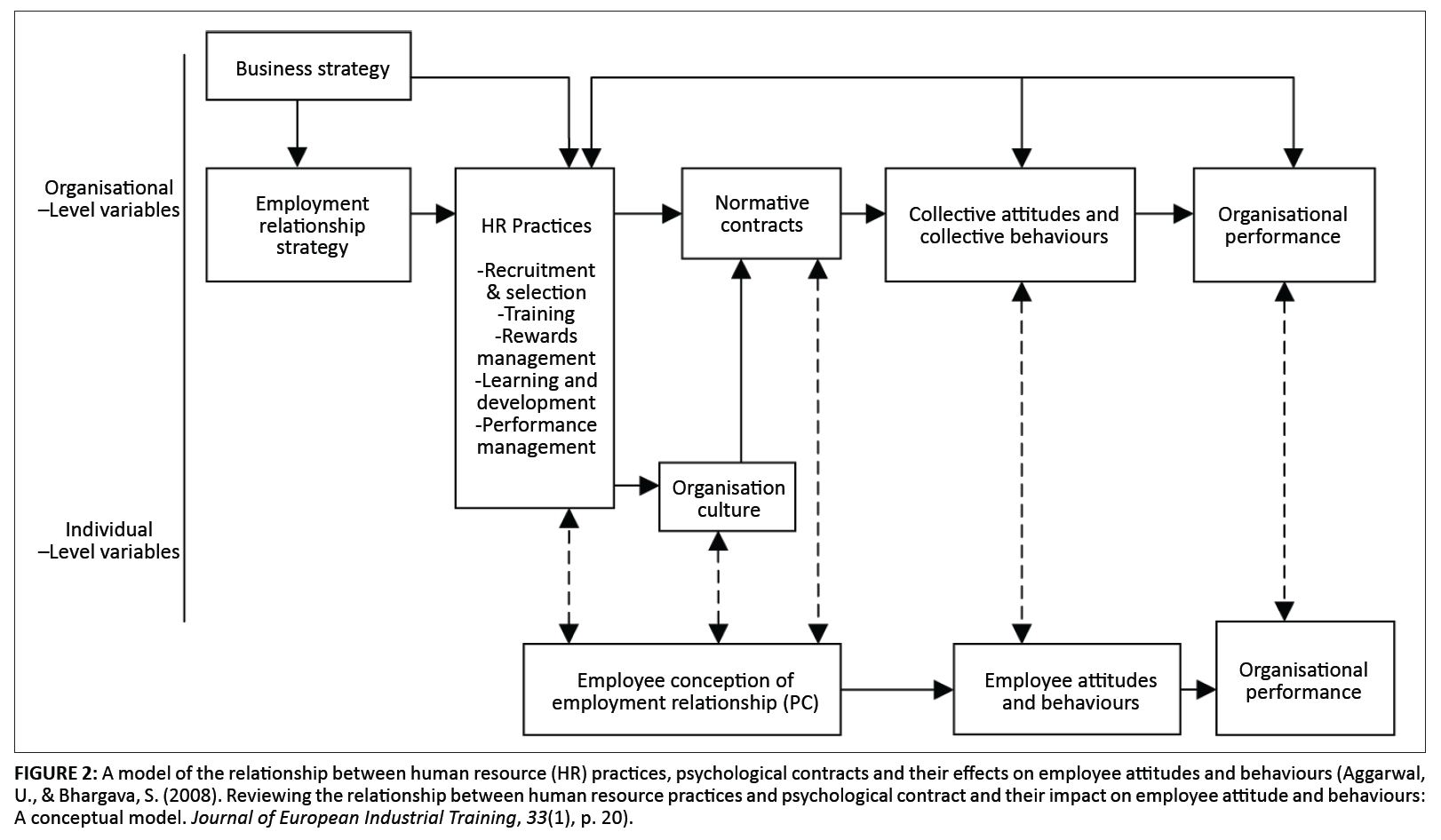

Human resource practices send strong messages about what organisations expect and what employees can anticipate in return (Guest, 1998; Rousseau & Greller, 1994). They are major mechanisms employees use to understand the terms of their employment (Rousseau, 1995; Rousseau & Wade-Benzoni, 1994). Furthermore, human resource practices create contractual and future intentions through hiring practices, reward practices and developmental activities. Organisations even use them as communication tools (Guzzo & Noonan, 1994; Lucero & Allen, 1994; Rousseau & Greller, 1994; Sims, 1994). Several studies confirm the influence of these human resource practices on organisational performance (Ahmad & Schroeder, 2003; Allen & Griffeth, 1999; Chang & Huang, 2005; Huselid, 1995; Khatri, 2000; Xirogiannis, Chytas, Glykas & Valiris, 2007). The high cost of recruitment and selection (Pfeffer, 1998), the lag and productivity loss during the induction period (Davies, 2001), the loss of business opportunity (Walker, 2001) and poor customer relationships (Clarke, 2001; Messmer, 2000) highlight the importance of retaining committed employees (Chew & Chan, 2008). Figure 2 lists some of these human resource practices. They include providing equitable remuneration (Boyd & Salamin, 2001), recognising the efforts and contributions of employees (Davies, 2001), providing opportunities for training and career development (Chew & Chan, 2008) and shaping employees’ attitudes and behaviour (Whitener, 2001). The recruitment process is the employees’ first communication with the organisation. Therefore, it influences their attitudes and behaviour significantly (Aggarwal & Bhargava, 2008; Morrison & Robinson, 1997). Moreover, Suazo, Martinez and Sandoval (2009) emphasise the effect of induction on employees’ perceptions of the organisation. New work experiences, interesting assignments, skills-based training in line with an organisation’s business objectives and a planned career path also signal the organisation’s intention to foster a long-term employment relationship (Aggarwal & Bhargava, 2008; Martin et al., 1998; Sims, 1994). In addition, Rousseau and Ho (2000) and Robinson (1996) confirm that compensation and benefits have a major effect on the employment relationship from the outset. Performance-management practices also play key roles in determining employee-employer expectations (Aggarwal & Bhargava, 2008; King, 2000). Maguire (2002) emphasises that world class organisations invest in their people by aligning these human resource practices strategically. Figure 2 illustrates Aggarwal and Bhargava’s (2008) conceptual model. It explains the links between human resource practices, psychological contracts and employees’ attitudes, behaviour and organisational performance. Aggarwal and Bhargava (2008) explain the central role that human resources play in influencing psychological contracts and organisations’ performance. Figure 2 illustrates that an organisation’s business strategy directly influences its employment relationship strategy, which human resource practices (like recruitment, training and development, learning and performance management) implement. On an individual level, these human resource practices influence the employee’s understanding of the employment relationship or psychological contract. However, the conceptual model does not specify which of these human resource practices has the strongest relationship. Nevertheless, the model demonstrates the influence of psychological contracts on employees’ attitudes and behaviours and the performance of organisations. The model also illustrates that human resource practices lead to normative contracts and affect organisational culture. They, in turn, lead to shared attitudes, behaviours and improved organisational performance. This study contributes to the body of knowledge on psychological contracts and their relationships with human resource practices. An empirical study was necessary to examine which human resource practices have the strongest influence on the shaping of psychological contracts.

|

FIGURE 2: A model of the relationship between human resource (HR) practices, psychological contracts and their effects on employee attitudes and behaviours (Aggarwal,

U., & Bhargava, S. (2008). Reviewing the relationship between human resource practices and psychological contract and their impact on employee attitude and behaviours:

A conceptual model. Journal of European Industrial Training, 33(1), p. 20).

|

|

The researchers developed the five research proposals that follow from their review of relevant literature and used them when compiling this study’s questionnaire.• Proposal 1. Four types of psychological contracts exist in the organisation: transactional, transitional, balanced and relational.

• Proposal 2. Efficient training and development practices are important requirements for establishing relational psychological contracts.

• Proposal 3. An optimal performance-appraisal practice is an important requirement for establishing relational psychological contracts.

• Proposal 4. Remuneration practices are important requirements for establishing transactional and transitional psychological contracts.

• Proposal 5. An excellent communication practice is an important requirement for establishing relational and balanced psychological contracts. The next section explains the research design the researchers used to test these proposals.

Research approach

In order to answer the research question about the relationship between psychological contracts and human resource practices, it was essential to gather data on psychological contracts and human resource practices. The literature review revealed four types of contracts and between four and six human resource practices. To investigate a relationship between so many factors, the researchers needed quantitative data and descriptive analysis. There have been qualitative conceptual studies and the researchers needed empirical data to verify their findings. It was essential to use existing questionnaires to ensure the validity of this study and to ensure that it measures what it professed to. This was to investigate psychological contracts and human resource practices. Once the university’s ethical committee had granted ethical clearance, the researchers conducted a survey using a pre-tested quantitative questionnaire. The ethical committee was convinced that the research would not harm or disadvantage respondents and the respondents gave their consent to participate in the survey. The company also gave permission to use its information in the study and subsequent academic journal articles. The researchers offered no inducement to participate in the study. They did not ask for, or record, names and only used aggregated information in the study. The researchers thought that an electronic survey would be suitable because it: • does not have interviewer influence

• is accessible

• provides geographical flexibility (the population was spread over three provinces)

• ensures the anonymity of the respondents

• is cost-effective, as Zikmund (2003) described. The researchers collected quantitative data from the survey. The research approach ensured the reliability of the study because other researchers could easily repeat the study by using the existing questionnaire.

Research method

The researchers identified human resource practices (training and development, performance appraisals, reward and communication) as independent variables because they influence the type of psychological contract, which they identified as the dependent variable. Research participants

The target population and unit of analysis for this study consisted of knowledge workers at an iron ore mining company in South Africa. The researchers drew this sample from the organisation’s employee database. The knowledge worker sample had the characteristics that follow. They: • all had been with the organisation for more than one year

• all had a qualification (diploma or degree)

• were from all levels in the organisation

• were involved in complex work that requires making decisions

• all participated in performance appraisals

• were engaged in inter-functional activities

• were familiar with all human resource practices. To investigate such a large sample, the researchers sent questionnaires to all these knowledge workers – 936 in total. The final sample included 302 useable questionnaires. This was a 32% response rate and adequate for statistical analysis (Yehuda, 1999). Measuring instruments

Investigating the relationship between psychological contracts and human resource practices required a survey instrument that included both these elements. The researchers used existing and credible questionnaires that had been widely researched. The questionnaire they used in this study consisted of three sections: • demographic information, like age, gender, qualification, race, position, supervision, geographical area and tenure

• types of psychological contracts

• human resource practices. Types of psychological contracts: The researchers assessed the types of psychological contracts using Rousseau’s PCI (2000). There were 73 questions in this section. An example is ‘To what extent have you made the following commitments or obligations to your employer?’ The researchers used a 5-point Likert scale for the assessment: 1 for ‘not at all’, 2 for ‘to a small extent’, 3 for ‘to a moderate extent’, 4 for ‘to a large extent’ and 5 for ‘to a very large extent’. Researchers have used the questionnaire extensively in international (Dabos & Rousseau, 2004; Hui, Lee & Rousseau 2004; Rousseau, 2000) and in South African studies (Maharaj, 2003; Wöcke & Sutherland, 2008). It assessed the employees’ and the employer’s obligations, psychological contract transitions and psychological contract fulfilment. Contemporary researchers on psychological contracts, like Freese and Schalk (2008), confirmed that the PCI is based on theory and is therefore conceptually valid. The inventory also covers the employees’ and the employer’s obligations (Rousseau & Wade-Benzoni, 1994). As Rousseau’s research involved knowledge workers, the inventory was applicable to this study. Rousseau (2000) published a reliability alpha coefficient of 0.7. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the four types of contracts were high. On the subscales, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were generally acceptable, except for the transactional contract factors. The results section lists the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients the researchers obtained for the PCI in this study. Arnold (1996) emphasises that the results of empirical research on these types of contracts remain inconclusive and that the results often do not cross-validate. He describes the instability of the transactional and relational factors and difficulties in replicating studies. However, Rousseau (2000) claims that the PCI has construct validity and that one can generalise many aspects of the conceptualisation and operationalisation of psychological contract dimensions across societies. She published extensive factor analyses for discriminant and convergent validity. The other instrument the researchers used in this study was the Human Resource Practices Scale. Human resource practices: Researchers have used the Human Resource Practices Scale of Geringer et al. (2002) widely to measure the effect of human resource practices. Von Glinow, Drost and Teagarden (2002) claim that their major study on the scale in 40 countries offers solution methodology for conducting globally distributed human resource practices research. Content experts from six continents developed the Human Resource Practices Scale. Although practitioners from West and East Africa were included, South Africa was unfortunately not included in the global research project. The researchers in this study contributed to the body of knowledge on global human resource practices. There were 50 questions in this section of the questionnaire for this study, derived from the Human Resource Practices Scale. An example is: ‘How accurately do the following statements describe your organisation’s practices?’ The researchers also used a 5-point Likert scale in this part of the survey: 1 for ‘not at all’, 2 for ‘to a small extent’, 3 for ‘to a moderate extent’, 4 for ‘to a large extent’ and 5 for ‘to a very large extent’. The next sections discuss the instrument’s reliability and validity. The original global study, of Geringer et al. (2002), intended to compare human resource practices in different countries meaningfully. The reliability of the findings in different settings was important. Therefore, the scale was tested in both developing and developed countries (Geringer et al., 2002). Von Glinow et al. (2002) warn against the measuring scale, instead of the research question, becoming the driver of the study. They also state that it is no longer enough simply to enter a new culture with a survey instrument developed and implemented in, for instance, North America. The scale includes approximately 10 items per human resource practice to improve the reliability of the instrument. Although Geringer et al. (2002) did not publish internal reliability coefficients, the researchers chose this scale on human resource practices because of its relevance and content validity. Von Glinow et al. (2002) and Drost, Frayne, Lowe and Geringer (2002) published articles based on their research on the Human Resource Practices Scale. In this South African study, the researchers found high Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all five human resource practices. However, high reliability coefficients do not imply high validity. The items in the questionnaire were developed from grounded theory and the inputs of subject matter experts from the 40 different countries. Geringer et al. (2002) claim high content validity through the scale’s rigorous refinement and piloting processes. Translation was not an issue in this study, as it was in the global study, because all respondents were first- or second-language English speakers. Geringer et al. (2002) give evidence of triangulation to improve the content validity of the scale. Drost et al. (2002) and Von Glinow et al. (2002) operationalised the scale with their results, thereby providing further empirical evidence of construct validity. In this study, the researchers conducted exploratory factor analysis on these practices to validate the findings further. The questionnaire the researchers used for this study consisted of the three sections described earlier. The researchers piloted it with respondents from the sample and tested it for simplicity, understanding and completion time. The following section discusses the research procedure. Research procedure

The researchers identified employees that fit the criteria, as discussed in the section on research participants, for the research sample from the organisation’s employee database. They sent emails, with links to the web-based electronic survey, to these knowledge workers. It took between 30 and 45 minutes to complete the survey. The researchers sent reminders to the participants two weeks after distributing the questionnaire and a final reminder five days before the survey closed. They captured the data in Excel and conducted the statistical analysis afterwards. Statistical analysis

The researchers performed data analysis to determine: • the response rate and omissions

• the demographics of the sample

• the type of psychological contracts the participants had

• the effect of the sample’s demographics on the types of psychological contracts

• the effect of human resource practices on the different psychological contracts. They divided the questions in the questionnaire into categories, as prescribed by Rousseau (2000), to assess psychological contracts. To test for differences between employee and employer variables, the researchers performed a paired t-test to determine whether there is any significant difference at the 5% level. The researchers used the following formula to determine the types of psychological contracts: PC = {> (balanced; relational; transactional; transitional)} Where: • ‘PC’ denotes psychological contract

• ‘Balanced’ denotes mean

• ‘Relational’ denotes mean

• ‘Transactional’ denotes mean

• ‘Transitional’ denotes mean. The greater mean value between the four contract types defines the PC of a respondent. Furthermore, the researchers performed an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the effect of human resource practices on psychological contracts. The researchers then performed Duncan’s multiple range test to determine the means of respondents with a particular contract for each human resource practice. The researchers used chi-square and Pearson correlations to test for significance at the 0.05 level (Zikmund, 2003). The next section gives the results of these descriptive and inferential statistical analyses.

This study set out to investigate the relationship between psychological contracts and human resource practices. The previous section presented the research design. This section presents the survey response rates, the demographic analysis and the corresponding results. Tables 1 to 11 give the results of the statistical analysis. Tables 1–7 give the perceptions of the employees’ and the employer’s obligations and compare them. These tables illustrate the conclusions about the first proposal on the four types of psychological contracts that could possibly exist in the organisation. The researchers paid special attention to the reliability and validity of the assessment instrument. Tables 8–11 illustrate the types of psychological contracts and the effects that human resource practices have on them in order to highlight the conclusions for the other four proposals. The next section presents the results of the demographic analysis. The article then presents the tables.

Demographics

The smallest percentage of respondents (10%) was younger than 30 years of age. However, the percentages in the rest of the age groups were evenly distributed. Most of the respondents were White (71%) and male (74%). This is consistent for workers in the mining industry and South African knowledge worker populations (Strong, 2003; Wöcke & Sutherland, 2008). The respondents were evenly distributed across the qualification categories. Most (29%) had diplomas. The positions of the respondents in the organisation were evenly distributed. Senior managers had the lowest percentage (15%). This is consistent with industry norms. Most of the sample (62%) had people who reported to them. Most of the sample (65%) had spent more than 10 years with the organisation and 26% of the sample had been with the organisation for more than five years.

Conclusions for proposal 1 – four types of psychological contracts exist in the organisation: Transactional, transitional, balanced and relational

Psychological contracts comprise perceptions about the employees’ and the employer’s obligations. The researchers used Rousseau’s questionnaire (2000) with a standardised method of analysis. In order to ascertain the four types of psychological contracts, the researchers reviewed the perceptions about employees’ obligations to the organisation, the employer’s obligations to the employees and the differences between them.

Perceptions of employees’ obligations

The researchers analysed the perceptions of the employees’ obligations and present the results in this section. Table 1 illustrates the findings about employees’ obligations to the organisation and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Before discussing the descriptive statistics for the perceptions of the respondents, the reliability and validity of the scales require attention. Rousseau (2000) reports that, although several scales did meet the traditional standards for reliability, problematic scales in her study were ‘employer narrowness’ and ‘employee stability’. In her study, ‘short term’ also yielded an alpha coefficient of 0.69 for four items, whilst a three-item version met reliability standards. However, in the later version of the PCI (Rousseau, 2008), which this study used, four items were again included under ‘short term’. Finer analysis of the item frequencies yielded interesting patterns. Where the alpha coefficients were low, the pattern of responding showed that participants usually chose one point on the scale. For items under ‘short term’, for example, between 45% and 63.91% of the respondents chose 1 (‘not at all’) on the scale. The same pattern occurred for ‘loyalty’. The participants consistently answered 4 (‘to a large extent’) on items like ‘make personal sacrifices for this organisation’ and ‘take this organisation’s concerns personally’. These low variances in the answers could also have contributed to lower alpha coefficients. The researchers needed to conduct factor analysis to investigate these findings. They identified a 6-factor solution, with one item loading onto a seventh. This is similar to Rousseau’s (2000) findings. Table 2 gives the factor analysis for employees’ obligations. One could describe the seven factors the researchers identified as: • ‘development external’ (factor I)

• ‘security’ (factor II)

• two items from ‘dynamic performance’ (factor III)

• ‘short term’ and ‘narrow’ loaded onto the same factor (factor IV)

• ‘loyalty’ combined with two factors of ‘dynamic performance’ (factor V)

• ‘development internal’

• negative loading on two items of ‘short term’ (factor VI)

• ‘Fulfil a limited number of responsibilities’ (factor VII). The factor correlation for rotated factors showed that there is a relationship between factors III and V, with a coefficient of 0.55. The four items of ‘dynamic performance’ were split between these factors. The eigenvalue for factor I was 6.44 and explained 21.01% of the variance. The seven factors explained 45.04% of the variance. Rousseau (2000) also reports that, in a Singapore sample, divergent patterns emerged, like a 3-factor solution for employer obligations and a five-factor solution for employee obligations. This study revealed similar trends, where contract forms collapsed to load onto the same factors, like ‘short term’ and ‘narrow’. Although there was a departure from a single structure in this study, the results generally fell within the psychological forms that Rousseau (2000) reports. Rousseau has conducted research to improve the measurement of ‘short term’ (transactional contracts). Freese and Schalk (2008) warn against adding or deleting items to fit a particular setting. Therefore, the researchers used the current format of Rousseau’s (2008) questionnaire in this study. The standard deviation was high for most dimensions. The mean for ‘career development – external market’ was 2.77. This showed that employees did not build contacts or skills that would improve their employment opportunities outside the organisation. The standard deviation, however, was 0.9, and showed that some respondents were preparing themselves for possible employment at other organisations. ‘Dynamic performance requirements’ had a mean of 4.14 and a standard deviation of 0.55. Employees were obliged to perform in order to achieve new and more demanding goals to help the organisation become and remain more competitive (Rousseau, 2000). They were willing to go out of their way to ensure the success of the organisation at their own cost. ‘Career development – internal market’ had a mean of 4.03 and a standard deviation of 0.63. The employees felt that they were obliged to seek development opportunities, build skills and make themselves increasingly valuable to their current employer. Furthermore, there was a moderate relationship between the employees’ willingness to accept challenges (‘dynamic performance requirements’) and seeking out development opportunities (‘career development – internal market’). The Pearson correlation coefficient between ‘dynamic performance requirements’ and ‘career development – internal market’ was 0.5965 with a probability of < 0.0001. Most of the employees tended to show ‘loyalty’ to their employer, with a mean of 4.03 and a standard deviation of 0.61. Employees would make personal sacrifices for the organisation and protect its image because they were emotionally involved with it. ‘Loyalty’ had a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.5638 and a probability value of < 0.0001 with ‘security’. This showed that there is a moderate relationship between employees’ commitment and their intention of staying indefinitely at the organisation. Employees showed that they felt obliged to stay with the organisation for a long time and had not made plans to work elsewhere. This was clear in the ‘security’ dimension, where the mean was 3.66. However, the standard deviation was 0.9. The mean for ‘short term’ employment with the organisation was 1.97 and the standard deviation was 0.69. This showed that employees did not intend to leave their current jobs. The same trend emerged for the ‘narrow’ dimension, where the mean was 1.84 and the standard deviation was 0.66. This was an indication that employees were prepared to have a broader job description than their contracts stipulated for the good of the organisation. The employees felt an obligation to their employer. The researchers also needed to ascertain the perceptions of the employer’s obligation. The next section gives their findings. Perceptions of employer’s obligations

Table 3 gives the results for each of Rousseau’s psychological contract dimensions for employer’s obligations, as the employees perceive them, as well as the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Finer analysis of the item frequencies revealed a pattern. Where the alpha coefficients were low, the pattern of answering showed that participants usually chose one point on the scale. For example, the answers to the item ‘short-term employment’ (employer obligation to employee) showed that 52.32% of the respondents chose 1 (‘not at all’) on the scale. This was also true for item ‘a job for a short time only’, where 63.91% chose 1. The researchers conducted an exploratory item-level factor analysis on employer’s obligations. They found a 5-factor solution, similar to Rousseau’s (2000) study. Table 4 shows the principle factoring axis analysis. In this study, the researchers neatly defined the three psychological contracts by principal axis factoring. The fourth contract had a very low representation in the sample and the researchers concentrated on the other three. The five factors were: • ‘dynamic performance requirements’

• ‘career development – internal market’

• items of ‘career development – external market’ (factor I — balanced contract)

• ‘loyalty’

• ‘security’ (factor II – relational contract). Two items of ‘career development – external market’ loaded on their own as a separate factor. These were: • ‘potential job opportunities outside the organisation’ and ‘contacts that create employment opportunities elsewhere’ (factor III)

• ‘short term’ and ‘narrow’ (factor IV – transactional contract). A single item, ‘Help me to respond to ever greater industry standards’, also loaded slightly onto a fifth factor (factor V). Two items on ‘career development – external market’ loaded onto the same factor as ‘internal development’. This was similar to Rousseau’s findings (2000). The eigenvalue of factor I was 10.2657 and explained 34.93% of the variance. The five factors the researchers identified in this study explained 50.49% of the variance. Furthermore, items from ‘dynamic performance requirements’, ‘career development – internal market’ and ‘career development – external market’ loaded onto this factor. The correlation coefficient for factors I and II was 0.62. This shows that there is a relationship between the elements of the balanced and relational contracts. For example, Rousseau’s Singapore study also showed convergence between the balanced contract forms. Rousseau (2000) explains that societal differences or lower levels of variation in the kinds of psychological contract forms and human resource strategies could cause this. This study endeavoured to investigate the effect of these human resource strategies on psychological contracts. Therefore, the researchers used Rousseau’s version (2008) of the questionnaire. The average standard deviation for the employer’s obligation variables was 0.82. Employees’ perception of their employer’s obligation, in terms of ‘career development – external market’, was that the employer was not doing enough to help them to find external job opportunities. The mean for this dimension was 2.57 and the standard deviation was 0.85. The employer did not allocate job assignments to them or inform them of opportunities outside the organisation. The employer also did not give them contacts that could create employment opportunities elsewhere. With regard to ‘dynamic performance requirements’, employees felt that the employer helped them to achieve their highest possible levels of performance in the organisation. The mean for this dimension was 3.3, with a standard deviation of 0.87. This also shows that some employees disagreed with this sentiment. However, the general results showed that employees believed that the employer enabled them to adjust to new and challenging performance requirements. With regard to the dimension of ‘career development – internal market’, employees thought the employer granted them opportunities to develop their careers; it yielded a mean of 3.28. The standard deviation of 0.9 showed that some employees disagreed. The mean for ‘loyalty’, based on employees’ perception of the employer’s obligation, was 3.3. It had a standard deviation of 0.87. Most employees felt that the employer showed some loyalty to them regarding their personal welfare. The employees believed that the employer made decisions that were in their (the employees’) best interests. The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient between ‘career development – internal market’ and ‘loyalty’ was 0.70739, at a probability of < 0.0001. This showed a relationship between these two dimensions of psychological contracts. The respondents saw the employer’s decisions as being in their best interests in many instances and relevant to their career development. Furthermore, there was a correlation coefficient between ‘career development – internal market’ and ‘dynamic performance requirements’, of 0.89174 at a probability of < 0.0001. This showed that the support they receive from the organisation to meet challenges has influenced their perception of career opportunities in the firm. Employees perceived their employment in the organisation as secure and felt that they had stable benefits for their families. The mean for ‘security’ was 3.57, with a standard deviation of 0.78. Their tenure in the organisation confirmed this, as 65% of the sample had been with the organisation for more than 10 years. Most of the workforce did not believe that the employer had ‘short term’ objectives for them. It had a mean of 1.99 and a standard deviation of 0.72. In general, employees felt that the employer had tried to retain them in the organisation. As with the ‘security’ dimension, employees believed that the employer involved them in organisational matters and broadened their job descriptions to advance their careers. However, these results do not show whether there were significant differences between the perceptions of employees’ and the employer’s obligations. The next section compares these perceptions. Comparisons between the employees’ and the employer’s obligations

Table 5 gives the findings of the t-test on the comparisons between the employees’ and the employer’s obligations. Where the p-value (probability value) was less than 0.05, there was a significant difference between the two variables at the 5% level. ‘Loyalty’, ‘narrow’, ‘dynamic performance requirements’ and ‘career development – internal’ and ‘career development – external’ showed significant differences between the employees’ and the employer’s obligations at the 5% level. For ‘short term’, there was no significant difference between the perceptions of the employees’ and the employer’s obligations. The belief that the employer intended to retain their services in the long term supported the employees’ intention to stay with the organisation for the long term. There was a significant positive difference for ‘loyalty’. This shows that the employees believed that they showed more loyalty to the organisation compared to the loyalty it showed them. Again, as in the case of ‘short term’ employment, there was no significant difference in perceptions of ‘security’. To conclude this section, the employees still believed that they were contributing more in each of these dimensions than the employer was. From their perspective, the employer could do more for the relationship than was currently the case. Given these findings, the researchers examined the different psychological contracts. The next section gives these results. Findings on the types of psychological contracts

Proposal 1 suggested that all the types of psychological contracts exist in the organisation. Table 6 shows the different psychological contracts that the researchers found. The alpha coefficient for transactional contracts was 0.69. Therefore, the researchers had to view the results for this contract cautiously. They needed factor analyses to evaluate their validity. In Rousseau’s (2000) study, the findings on the transactional contract were also interpreted with difficulty. Most of the sample (69%) had relational contracts with the organisation. Balanced contracts followed, with 22% of the sample. Approximately 8% of the sample had transitional contracts whilst only 1% had transactional contracts. The researchers conducted an analysis of the effect of demographical factors, like gender, qualifications, supervision and tenure, on the type of psychological contract. This examination helped to identify the factors that contributed to the kind of contract. The researchers performed a chi-square test of dependency (Zikmund, 2003) on the effect of demographic groupings on the types of psychological contracts. There was no significant relationship between gender and type of psychological contract at the 5% level, as well as for position in the organisation. However, in the case of supervisory responsibilities, the chi-square test gave a chi-square statistic of 6.03 at 2 degrees of freedom. This had a probability level of 0.0491 and showed that there was a significant relationship between supervision and type of psychological contract for respondents who had balanced or relational contracts and supervisory responsibilities. Employees with transitional contracts had no supervisory responsibilities. For length of tenure, the chi-square test yielded a chi-square statistic of 20.86 at 4 degrees of freedom and a probability level of 0.0003. It showed a significant relationship between length of tenure and type of psychological contract. Respondents with more than 10 years of service dominated the relational and transitional contract groups. In the balanced contract group, a large percentage (38.81%) of the respondents fell into the 0–5 year group. The chi-square test on race groupings yielded a chi-square of 38.18 at 6 degrees of freedom at a probability level of < 0.0001. This showed a significant relationship at the 5% level. White people had a majority in the relational contract groups. However, in the balanced and transitional contract groups, the proportions of Black people were 38.81% and 25.93% respectively. Relational contracts are open-ended and less specific agreements that establish and maintain relationships (Robinson & Rousseau, 1994). The two dimensions for relational contracts were ‘security’ and ‘loyalty’. Tenure had a significant effect on the formation of a relational contract. Of the relational group, 72% had been with the organisation for more than 10 years. Employees with fewer than five years’ service had a relatively low number of relational contracts compared to other contract groups. White people had the highest number of relational contracts. The literature defines balanced contracts as dynamic and open-ended employment arrangements. The three dimensions for balanced contracts were ‘career development – external’, ‘career development – internal’ and ‘dynamic performance requirements’. Approximately 23% of the sample had balanced contracts in the organisation. The employer was willing to help employees achieve long-term employability outside the organisation as well as within it. The employer expected employees to develop skills that were marketable outside the organisation and those that were valuable to the organisation. The employer required ‘dynamic performances’ from the employees. It expected them to perform new and challenging tasks. The employees also had to prove that they were flexible in their work because their job descriptions could change. With regard to support, the employer had made a commitment to assist employees to learn and develop new skills continuously. As with relational contracts, supervision affected the formation of balanced contracts in the workplace. Balanced contracts were more relevant to employees who were supervisors than to others. Tenure did not have a significant effect on the formation of balanced contracts compared to relational contracts. Both parties contributed to learning, whether for external or internal employability. This was appealing to employees with fewer than five years’ tenure, compared to the relational contract groups where the emphasis was on security. Black people had more balanced contracts than other types. Of the sample with balanced contracts, 39% were Black people. This was a substantial figure compared to relational contract groups. Wöcke and Sutherland (2008) state that the high turnover of Black managers shows the strong influence a favourable labour market place has on Black people. The employer expected them to train and develop skills for internal as well as external employability. Rousseau (1995, 2004) emphasises that the transitional contract is not actually a psychological contract. Instead, it is a cognitive state that reflects the consequences of organisational change and transitions that are at odds with a previous employment contract. The questions in the questionnaire did not distinguish between employees’ perceptions of employees’ and employer’s obligations in transitional contracts. Therefore, the researchers present the findings on transitional contracts separately from those on the other contracts. Table 7 provides the findings for transitional psychological contracts. The means of these dimensions were consistent. However, they had high standard deviations. Approximately 8% of the sample had transitional contracts. This is low when one compares it to the two contract types discussed earlier. The relevant dimensions for this type of contract are ‘no trust’, ‘uncertainty’ and ‘erosion’. The Cronbach alpha coefficients were high for all three dimensions. The factor analysis revealed that one factor (transitional contract) explains 49% of the variance and has an eigenvalue of 6.36028. The Pearson correlation coefficient statistics showed high correlations between the responses to these three dimensions. The Pearson correlation coefficient between ‘uncertainty’ and ‘no trust’ was 0.77285 at a probability of < 0.0001, whilst that between ‘erosion’ and ‘uncertainty’ was 0.70216 at a probability of < 0.0001 and that between ‘no trust’ and ‘erosion’ was 0.61984 at a probability of < 0.0001. This shows that respondents who distrusted the organisation probably also experienced uncertainty and erosion in their relationship with the employer. Employees with transitional contracts tended to have fewer supervisory functions compared to those with relational and balanced contracts. Of these employees, 60% were not supervisors. Tenure tended to have a significant difference. Employees with more than 10 years of service seemed to dominate the transitional contract groups (51%). As 52% of employees with transitional contracts had more than 10 years of service, it is possible that these employees were very close to retirement and were preparing to leave the organisation. Racial distribution also had a significant difference at the 5% level. Of the employees with transitional contracts, 52% were White. Affirmative action policies might influence this factor (Wöcke & Sutherland, 2008). Employees in first-line management and subordinates make up 52% of workers with transitional contracts. It was not possible for the researchers to perform a statistical analysis of employees with transactional contracts because of the small number of respondents. The second largest mean meant that all three respondents had transitional contracts. Therefore, the researchers conducted an analysis on three contract groups. Sixty-seven had balanced contracts, 208 had relational contracts and 27 had transitional contracts. In addition to the types of psychological contracts, the researchers investigated the relationship between these contracts and specific human resource practices. The next section presents the results.

|

TABLE 1: Perceptions of employees’ obligations.

|

|

TABLE 2: Pattern of rotated factor loadings for employees’ obligations.

|

|

TABLE 3: Perceptions of employer’s obligations.

|

|

TABLE 4: Pattern of rotated factor loadings for employer’s obligations.

|

|

TABLE 5: Paired t-test at a significance level of 5%.

|

|

TABLE 6: Types of psychological contracts.

|

|

TABLE 7: Transitional psychological contracts.

|

Findings for proposals 2–5 on the relationship between human resource practices and types of psychological contracts

The reliability and validity of the Human Resource Practices Scale (Geringer et al., 2002) needs to be established before a discussion of the relationship between the types of psychological contracts and human resource practices is possible. Table 8 gives the results of the reliability study and Table 9 the results of the validity study. The researchers found a five-factor solution. The five factors could explain 43.12% of the variance. All items assessing ‘performance appraisal’ loaded onto factor I. This factor also explains 24.74% of the variance. The item that describes the purpose of performance appraisal as ‘for salary administration’ loaded slightly onto ‘remuneration practices’. However, there were nine other factors with high loadings. The items that assessed ‘training and development’ loaded onto factor II. One item, ‘provide a reward to employees’, was very low. Items on ‘communication’ loaded only onto factor III except for the item ‘too many people need to be consulted before you can do anything here’, which loaded slightly onto ‘communication’. The item ‘informal communication works better here than informal communication does’ loaded negatively, yet loaded slightly onto ‘hiring practices’. All items that assessed ‘remuneration practices’ loaded onto factor IV. Factor V represented most of the ‘hiring practices’ items, except for three items that loaded onto ‘remuneration practices’. There was convergent validity between the items that loaded onto the same factor. Table 10 gives the factor correlations for rotated factors. This exploratory factor analysis showed that factor I (‘performance appraisal’), with a high eigenvalue, also correlated higher than any other factor with factors II, III, IV and V. Factor I correlated the highest with factor II (‘training and development’) and factor III (‘communication’). There was discriminant validity between the human resource practice scales, given by the five-factor solution. Table 11 gives the findings on how these human resource practices influenced psychological contracts and the level of significance of each practice. Means with different superscripts differed significantly at the 5% level. There was no significant difference between the means of balanced and relational contracts. However, transitional contracts differed significantly in almost all human resource practices except ‘remuneration’. The researchers provided the results of the different types of psychological contracts, as well as their relationships with human resource practices. The next section discusses the results systematically according to the proposals.

|

TABLE 8: Alpha coefficients of the Human Resource Practices Scale.

|

|

TABLE 9: Patterns in the rotated factor loadings for the Human Resource Practices Scale.

|

|

TABLE 10: Factor correlations for rotated factors.

|

|

TABLE 11: Relationship between human resource practices and psychological

contracts.

|

The study examined the types of psychological contracts that exist in an organisation and the relationships between these contracts and specific human resource practices. The previous sections gave the research methodology and results. This section categorises the results and discusses them by proposal.

Proposal 1

The research supported proposal 1 on Rousseau’s four types of psychological contracts that exist in organisations (1994). The contracts in the sample were skewed towards the relational and balanced psychological contracts. Supervision and tenure were important attributes in establishing relational psychological contracts. Therefore, organisations can benefit from development programmes on supervision. There were fewer previously disadvantage individuals (PDIs) with relational contracts. Organisations could develop PDIs for opportunities outside the organisations to establish relational contracts. Supervision, but not tenure, influenced employees with balanced contracts significantly compared to relational contracts. Black employees had a high percentage of balanced contracts and had opportunities for career development. Wöcke and Sutherland (2008) attribute this to the favourable market conditions that allow for mobility within and outside organisations. In order to change the balanced contracts of employees into relational ones, employers could consider giving PDIs opportunities to progress to supervisory positions. Employees with transactional contracts had the lowest number in the sample, whilst those with transitional contracts had only a small percentage. These employees did not hold supervisory positions in the organisation. Employees with higher tenures dominated the transitional contract group compared to those with fewer than five years’ service. White employees dominated the transitional contract group. This probably indicates the effects of affirmative action policies in South Africa (Wöcke & Sutherland, 2008). Organisational hierarchy influenced employees with transitional contracts because most of them fell into the bottom segment of the organisational structure. To move employees away from this type of contract, employers could invest in developing their careers.

Proposal 2

Proposal 2 states that efficient training and development practices are major requirements for forming relational psychological contracts. The results in Table 11 show that training and development were ranked first amongst employees with balanced and relational contracts and second amongst those with transitional contracts. Relational and balanced contracts had means of 3.5702 and 3.5776 respectively. This implies that employees thought that training and development had a significant effect on their contracts. The amount of training and development the employer was willing to invest in employees with relational contracts might have determined the amount of loyalty these employees had for the company. It might also have given these employees a sense of security. The employer would not develop them if it intended to break the employment relationship. Suazo et al. (2009) support this. They state that, since organisational funds are usually limited, spending funds on training may tell employees that the organisation values them and that they are likely to enjoy long-term or permanent employment. The ranking of training and development was high (second) for those with transitional contracts. The mean for these employees was 2.9296 – a difference of almost 0.7 compared to other employees. Employees with transitional contracts also value career development, possibly to prepare them for other employment.

Proposal 3

The results in Table 11 support proposal 3 that an optimal performance-appraisal practice is a major requirement for forming relational psychological contracts. Employees with relational and balanced contracts ranked performance-appraisal practices third. Both types of contract recorded means of approximately 3.3. However, employees with transitional contracts ranked it the lowest (fifth), with a mean of 2.596. Performance appraisals play key roles in determining employee-employer expectations and have a direct influence on other practices. The feedback from the performance-appraisal process relates directly to the terms and conditions of employment, like remuneration, promotion and training opportunities (Suazo et al., 2009). Employees with transitional contracts thought that performance appraisals had the least effect on their working relationships and did not value this practice.

Proposal 4

Proposal 4 states that remuneration is a major requirement for establishing transactional and transitional psychological contracts. The findings of the study supported this. Employees with transitional contracts thought that remuneration had the biggest effect (ranked first) of the human resource practices, with a mean of 3.0494. Employees with relational contracts thought it was the least important (fifth) practice and those with balanced contracts ranked it fourth, with means of 3.2345 and 3.2786 respectively. The relational contract’s dimension of stability addresses remuneration issues in the relational contract. Employees with relational contracts believed that the employer was committed to offering stable wages and long-term employment. Sauzo et al. (2009) state that the compensation systems, which create psychological contracts, are often implicit. They give two examples. Remuneration incentives, like merit pay increases, may signal that employees have stable or long-term employment with the organisation. However, benefits like retirement or health insurance may signal that organisations value their employees and they can therefore expect long-term employment. Employees with balanced contracts also saw remuneration practices as implied. In contrast, employees with transitional contracts saw remuneration as the most important human resource factor. Rousseau (2004) says these workers tend to perform in ways consistent with the contributions that organisations pay them to make. These employees know that organisations do not guarantee their employment.

Proposal 5

Proposal 5 suggested that excellent communication practice is a major requirement for forming relational and balanced psychological contracts. The results in Table 11 showed that workers with relational and balanced contracts ranked communication as the second most important practice in forming these contracts. Employees with relational and balanced contracts had means of 3.3517 and 3.3806 respectively. Employees with transitional contracts ranked it fourth, with a mean of 2.6296.Workers with relational contracts have emotional relationships with the organisation. They expect to represent the organisation and want to create a positive image of it. They are personally involved with the organisation and know that the organisation is also concerned about their well-being. Regular communication on matters that concern the organisation or its employees is essential to them. Employees with balanced contracts believe in career development. Therefore, communication about policies or changes in policies is important in determining their career plans. These employees are willing to accept new and challenging demands for the well-being of the organisation and feedback on organisational performance is important to them. On the other hand, employees with transitional contracts do not trust the employer. Therefore, they think that communication aims at misleading employees intentionally. These employees view procedures and policies negatively or as ways of limiting their freedom. Communicating with these employees may not benefit the organisation, as the relationship is beyond repair. Although the researchers did not include the dimension of hiring practices as one of the proposals, they included it in the study. Employees with relational contracts ranked hiring practices fourth, with a mean of 3.2601. Hiring practices had the least effect on employees with balanced contracts, who ranked them fifth. The practice had a mean of 3.2015 for employees with balanced contracts. This suggests that it had a moderate effect on these employees. Hiring creates the foundation for a psychological contract with an employee because it is the first intervention or communication with the potential employer (Arthur, 2001). Employees with transitional contracts showed a significant difference at the 5% level compared to employees with relational and balanced contracts, with a mean of 2.9185. Employees with transitional contracts ranked it third amongst the human resource practices, much higher than did employees with other types of contracts. This suggests that employees with transitional contracts found hiring practices more important than the other two contract groups did because they were looking for new employers. This section discussed the types of psychological contracts and their relationships with human resource practices. The next section contains a summary and the implications of the study.

Based on the findings in Table 11, Table 12 gives a summary of the human resource practices in order of importance for creating specific psychological contracts.Table 12 gives an insight into the effects of moving employees from one type of contract to another. It emphasises the effect of human resource practices on these contracts. Human resource practices could actually affect each other. For example, performance appraisal could have a direct effect on training, development and remuneration. Employers who have a long-term perspective prefer relational psychological contracts. Training and development had the highest effect on creating this type of contract, with communication having the second highest effect. Organisations also communicate through internal procedures and practices (Suazo et al., 2009) and may include employment benefits. Employees ranked performance appraisal third in its effect on relational psychological contracts. It could facilitate communication and move employees from a balanced to a relational contract (Schraeder, Becton & Portis, 2007). Hiring practices were fourth in affecting the formation of relational contracts, followed by remuneration. Tulgan (2001) suggests that employers should ensure employability through ongoing training and development, thereby avoiding employee turnover and the need for excessive hiring within the organisation. Remuneration was the human resource practice with the greatest effect on employees with transitional contracts. Training and development was second in its effect on creating transitional psychological contracts. Employees might have seen training as a means of empowering themselves for employment elsewhere. In conclusion, the following model illustrates the effect of human resource practices on the different psychological contracts. As the relationship with the employer improves (moving up the steps), the upper blocks require more investment. This will improve organisational performance (Aggarwal & Bhargava, 2008). The researchers developed this model (Figure 3) to illustrate how psychological contracts could move from red to green by investing in human resource practices. When the employer invests in training and development, communicates with employees and has a sound performance-appraisal procedure in place, the employer develops the employee further in terms of hiring or promotion and better remuneration. This leads to the establishment of relational psychological contracts.

|

TABLE 12: Human resource practices in order of importance for creating specific psychological contracts.

|

|

FIGURE 3: Model of the effect of human resource practices on psychological contracts.

|

|

Limitations of the study

The researchers conducted the research in a single organisation and limited it to the mining sector. Therefore, it did not give a clear perspective of different environments and cultures in different organisations or industries. It also focused only on knowledge workers. This makes it difficult to extrapolate the findings. In addition, the length of the questionnaire led to fatigue.

Recommendations for further research

Based on these limitations, the researchers recommend further research that includes different industries and blue-collar workers. Other researchers could then test the model of the effect of human resource practices on psychological contracts in different settings.

These research findings, with their limitations, assisted the researchers to understand the effect of human resource practices on forming psychological contracts. It supported the conceptual findings of Aggarwal and Bhargava (2008) with empirical data. Organisations could invest resources according to the model in Figure 3. In times of recession, organisations may decrease expenditure on training and development. Therefore, human resource practitioners need to note the possible implications of employee loyalty and breaching psychological contracts because of the strong relationship between training and development and relational contracts.

Aggarwal, U., & Bhargava, S. (2008). Reviewing the relationship between human resource practices and psychological contract and their impact on employee attitude and behaviours: A conceptual model. Journal of European Industrial Training, 33(1), 3–41.Ahmad, S., & Schroeder, R.G. (2003). The impact of human resource management practices on operational performance: Recognizing country and industry differences. Journal of Operations Management, 21, 19–43.

doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(02)00056-6 Allen, D.G., & Griffeth, R.W. (1999). Job performance and turnover: A review and integrative multi-route model. Human Resource Management Review, 9(4), 525–548.

doi:10.1016/S1053-4822(99)00032-7 Arnold, J. (1996). The psychological contract: A concept in need of closer scrutiny? European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 5, 511–521.

doi:10.1080/13594329608414876 Arthur, D. (2001). The employee recruitment and retention handbook. New York: Amacom. Boyd, B.K., & Salamin, A. (2001). Strategic reward systems: A contingency model of pay system design. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 77–93.

doi:10.1002/smj.170 Chang, W.A., & Huang, T.C. (2005). Relationship between strategic human resource management and firm performance. International Journal of Manpower, 26(5), 434–449.

doi:10.1108/01437720510615125 Chew, J., & Chan, C.A. (2008). Human resource practices, organisational commitment and intention to stay. International Journal of Manpower, 29(6), 503–522.

doi:10.1108/01437720810904194 Clarke, K.F. (2001). What businesses are doing to attract and retain employees — becoming an employer of choice. Employee Benefits Journal, 3, 34–37. Coyle-Shapiro, J.C., & Kessler, I. (2000). Consequences of psychological contract for the employment relationship: A large-scale survey. Journal of Management Studies, 37(7), 903–930.

doi:10.1108/01437720810904194 Dabos, G.E., & Rousseau, D.M. (2004). Mutuality and reciprocity in the psychological contracts of employees and employers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(1), 52–72.

doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.1.52, PMid:14769120 Davies, R. (2001). How to boost staff retention. People Management, 7, 54–56. De Meuse, K.P., Bergmann, T.J., & Lester, S.W. (2001). An investigation of the relational component of the psychological contract across time, generation, and employment status. Journal of Managerial Issues, 13, 102–118. Drost, E.A., Frayne, C.A., Lowe, K.B., & Geringer, J.M. (2002). Benchmarking training and development practices: A multi-country comparative analysis. Human Resource Management, 41(1), 67–86.

doi:10.1002/hrm.10020 Flood, P.C., Turner, T., Ramamoorthy, N., & Pearson, J. (2001). Causes and consequences of psychological contracts among knowledge workers in the high technology and financial services industries. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 12(7), 1152–1165.

doi:10.1080/09585190110068368 Freese, C., & Schalk, R. (2008). How to measure the psychological contract? A critical criteria-based review of measures. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(2), 269−286. Geringer, J.M., Colette, A.F., & Milliman, J.F. (2002). In search of ‘best practices’ in international human resource management: Research design and methodology. Human Resource Management, 41(1), 5–30.

doi:10.1002/hrm.10017 Guest, D. (1998). Is the psychological contract worth taking seriously? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 649–664.

doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(1998)19:1+<649::AID-JOB970>3.0.CO;2-T Guzzo, R., & Noonan, K. (1994). Human resource practices as communications and the psychological contract. Human Resource Management, 33(3), 44–72.

doi:10.1002/hrm.3930330311 Herriot, P., Manning, W., & Kidd, J.M. (1997). The content of a psychological contract. British Journal of Management, 8, 151–162.

doi:10.1111/1467-8551.0047 Hui, C., Lee, C., & Rousseau, D.M. (2004). Psychological contracts and organizational citizenship behavior in China: Investigating generalizability and instrumentality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(2), 311–321.

doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.2.311, PMid:15065977 Huselid, M.A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, production, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38(3), 635–672.

doi:10.2307/256741 Isaksson, K. (2005). Psychological contracts across employment situations: Psycons. Retrieved September 26, 2008, from www.uv.es\-psycon Khatri, N. (2000). Managing human resource for competitive advantage: A study of companies in Singapore. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(2), 336–365.

doi:10.1080/095851900339909 King, J.E. (2000). White-collar reactions to job insecurity and the role of psychological contract: Implications for human resource management. Human Resource Management, 39(1), 79–91.

doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-050X(200021)39:1<79::AID-HRM7>3.0.CO;2-A Lucero, M., & Allen, R. (1994). Employee benefits: A growing source of psychological contract violations. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(3), 425–446.

doi:10.1002/hrm.3930330310 Maguire, H. (2002). Psychological contracts: Are they still relevant? Career Development International, 7(3), 167–180.

doi:10.1108/13620430210414856 Maharaj, K. (2003). A comparative study of the psychological contract of white and black managers. Unpublished master’s thesis. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. Martin, G., Staines, H., & Pate, J. (1998). The new psychological contract: Exploring the relationship between job security and career development. Human Resource Management Journal, 6(3), 20–40.

doi:10.1111/j.1748-8583.1998.tb00171.x Messmer, M. (2000). Orientation programs can be key to employee retention. Strategic Finance, 81, 12–15. Morrison, E., & Robinson, S.L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of Management Review, 22, 226–256.

doi:10.2307/259230 Pfeffer, J. (1998). Seven practices of successful organizations. California Management Review, 40, 96–125. Robinson, S.L. (1996). Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 574–599.

doi:10.2307/2393868 Robinson, S.L., & Rousseau, D.M. (1994). Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 15, 245–259.

doi:10.1002/job.4030150306 Rousseau, D.M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. London: Sage. Rousseau, D.M. (2000). Psychological Contract Inventory. Technical report No. 2000-02. Pittsburgh, PA: Heinz School of Public Policy and Management, Carnegie Mellon University Press. Rousseau, D.M. (2004). Psychological contracts in the workplace: Understanding the ties that motivate. Academy of Management Executive, 18(1), 120–127. Rousseau, D.M. (2008). Psychological Contract Inventory: Employer and employee obligations. Pittsburgh, PA: Heinz School of Public Policy and Management, Carnegie Mellon University Press. Rousseau, D.M., & Greller, M. (1994). Human resource practices: Administrative contract makers. Human Resource Management, 33(3), 372–382.

doi:10.1002/hrm.3930330308 Rousseau, D.M., & Ho, V. (2000). Psychological contract issues in compensation. In S. Rynes & B. Gerhart (Eds.), Compensation issues in organizations: Current research and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Rousseau, D.M., & Wade-Benzoni, K. (1994). Linking strategy and human resource practices: How employee and customer contracts are created. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(3), 463–489.

doi:10.1002/hrm.3930330312 Schraeder, M., Becton, J.B., & Portis, R. (2007). A critical examination of performance appraisals. The Journal for Quality & Participation, 30(1), 20–25. Sims, R. (1994). Human resource management’s role in clarifying the new psychological contract. Human Resource Management, 33(3), 373–383.

doi:10.1002/hrm.3930330306 Strong, E.V. (2003). The role of the psychological contract amongst knowledge workers in the reinsurance industry. Unpublished master’s thesis. Gordon Institute of Business Science. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. Suazo, M.M., Martinez, P.G., & Sandoval, R. (2009). Creating psychological and legal contracts through human resource practice: A signalling theory perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 19, 154–166.

doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.11.002 Tulgan, B. (2001). Winning the talent wars. New York: Norton & Company. Von Glinow, M.A., Drost, E.A., & Teagarden, M.B. (2002). Converging on IHRM best practices: Lessons learned from a globally distributed consortium on theory and practice. Human Resource Management, 41, 123–140. Walker, J.W. (2001). Perspectives. Human Resource Planning, 24, 6–10. Whitener, E.M. (2001). Do ‘high commitment’ human resource practices affect employee commitment? A cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear modelling. Journal of Management, 27, 515–564.

doi:10.1177/014920630102700502, doi:10.1016/S0149-2063(01)00106-4 Wöcke, A., & Sutherland, M. (2008). The impact of employment equity regulations on psychological contracts in South Africa. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(4), 528–542. Xirogiannis, G., Chytas, P., Glykas, M., & Valiris, G. (2007). Intelligent impact assessment of HRM to the shareholder value. Retrieved September 20, 2009, from www.sciencedirect.com Yehuda, B. (1999). Response rate in academic studies: A comparative analysis. Human Relations, 52(4), 421−438.

doi:10.1023/A:1016905407491, doi:10.1177/001872679905200401 Zikmund, W.G. (2003). Business research methods. (7th edn.). Mason, OH: Thompson/South-Western. |