|

Orientation: Because workplace bullying has detrimental consequences on the profitability, work quality and turnover intention of organisations, this phenomenon should be addressed. Perceived Organisational Support (POS) was explored since factors such as role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships might act as buffers against workplace bullying, subsequently influencing the turnover intention of the organisation.

Research purpose: To investigate the role of POS as moderator in the relationship between workplace bullying and turnover intention across sectors in South Africa.

Motivation for the study: Workplace bullying is a worldwide concern and it is unclear whether perceived organisational support moderates the relationship between workplace bullying and turnover intention.

Research design, approach and method: A cross-sectional survey approach with a quantitative research design was used (N = 13 911). The South African Employee Health and Wellness Survey (SAEHWS) was administered to explore the experiences of bullying behaviour, POS and turnover intention.

Main findings: Bullying by superiors is more prevalent than bullying by colleagues. A positive relationship exists between workplace bullying and turnover intention. Role clarity, participation in decision-making and supervisory relationship moderates the relationship between bullying by superiors and turnover intention.

Practical/managerial implications: This study creates an awareness of the prevalence of workplace bullying in the South African context so that sufficient counteraction can be encouraged.

Contribution/value-add: This study contributes to the limited research regarding workplace bullying in the South African context by quantifying the relationships between workplace bullying POS and turnover intention.

Key focus of the study

Despite the increasing demands of the global world, which constantly generates new technological aspirations, work relationships are still recognised as a central component of workplaces worldwide. Workplace bullying by either an individual (Sperry, 2009) or multiple perpetrators (Namie & Namie, 2009) is increasing in the workplace. Experiences of bullying behaviour in the workplace are four times more prevalent than illegal forms of workplace harassment such as sexual harassment (Namie, 2007). Furthermore, bullying in the workplace is recognised internationally (Baillien, Neyens, De Witte & De Cuyper, 2009; Einarsen, Hoel & Notelaers, 2009;Lutgen-Sandvik & Sypher, 2009; Ortega, Høgh, Pejtersen & Olsen, 2009)and nationally(Pieterson, 2007; Wright, 2008) as a relevant and destructive phenomenon.

Most international studies have focused on the development and measurement of workplace bullying (Baillien et al., 2009; Einarsen et al., 2009; Namie & Namie, 2009), characteristics of workplace bullying (Lutgen-Sandvik & Sypher, 2009; Ortega et al., 2009 )and the different sectors experiencing workplace bullying (Bilgel, Aytac & Bayram, 2006; Bloisi & Hoel, 2008; Mathisen, Einarsen & Mykletun, 2008). This study will focus on two forms of workplace bullying, viz., experiences of bullying behaviour from superiors and experiences of bullying behaviour from colleagues. Furthermore, the study investigated whether perceived organisational support acts as a buffer against workplace bullying and endeavoured to show the relationship between workplace bullying and employee turnover intention.

Background to the study

In the context of Industrial Psychology, international research has shown a growing interest in workplace bullying(Agervold, 2007). Conversely, workplace bullying in South Africa is still in its infancy. This aggressive behaviour affects personal and professional relationships throughout an individual’s lifespan (Lewis, Coursol & Wahl, 2002)and if not recognised by organisations as a workplace phenomenon, it will increase. Workplace bullying occurs between superiors and their staff, and more recently, horizontally, which entails bullying among colleagues (Lewis & Sheehan, 2003). However, research has shown that abusive superiors have a more profound effect on employee commitment than experiencing abusive behaviour from colleagues (Koonin & Green, 2004; McCormick, Casimir, Djurkovic & Yang, 2006).

Nevertheless, if an organisation acts in a professional manner by providing the necessary support to workplace bullying targets, these supportive measures may enable employee coping mechanisms to deal with abusive behaviour in a constructive manner (Quine, 1999). Similarly, many researchers report that a lack of support is central to the inability of workplace bullying targets to cope with this phenomenon (Lewis & Orford, 2005; Leymann & Gustafsson, 1996; Matthiesen, Aasen, Holst, Wie & Einarsen, 2003). Then again, workplace bullying is under-reported and becoming an increasingly silent epidemic because of a lack of perceived organisational support and a fear of retribution (Koonin & Green, 2004;Lewis et al., 2002;MacIntosh, 2005;Strandmark & Hallberg, 2007). Consequently, the responsibility to cope with and report workplace bullying experiences does not rest only with the employee. It is also the responsibility of the organisation to protect employees against such actions in the workplace.

Namie (2000) acknowledges that 96% of co-workers are aware of the bullying target’s situation, suggesting that bullying is not a workplace secret. Even if co-workers do not witness workplace bullying, 87% of targets tell co-workers about their experiences. However, instead of protesting the bullying behaviour, employees on the sidelines often rally in support of the perpetrator; this is usually done because of a fear of punishment and as a way of self-protection. Because of this bullying, targets are incapable to form supportive coalitions with colleagues (Namie, 2000).

Workplace bullying is linked to various physical and psychological costs for the target, as well as organisational and social costs for the workplace. Consequences relating to the organisation include compensation for medical expenses (Bassman, 1992), and reduced productivity (Einarsen, Hoel, Zapf & Cooper, 2003) due to poor work performance. According to Einarsen et al. (2003) and Rayner and Keashly (2005), low-quality work, reduced productivity, high staff turnover and increased absenteeism are among the indirect costs to organisations. Targets contemplating strategies to cope with this destructive phenomenon found resignation to be an appropriate solution (Björkqvist, Österman & Hjelt-Bäck, 1994;Davenport, Schwartz & Elliott, 1999;Namie, 2000; Quine, 1999).

Research objectives

The primary objectives of this study were to determine whether perceived organisational support (role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships) moderate the relationship between workplace bullying (by superiors and colleagues) and turnover intention.

Trends from the research literature

Workplace bullying

Workplace bullying can be regarded as an element of aggressive behaviour that manifests in interpersonal work relationships between two individuals or between an individual and a group (Zapf & Einarsen, 2001). Rothmann and Rothmann (2006, p. 14) define bullying as ‘harassing, offending, and socially excluding someone at work to such a level that these actions negatively affect a person’s work tasks’. Thus, the label of the bully can be applied when a particular activity, interaction, behaviour or process has occurred repeatedly, frequently and over a period of time (Wood, 2008). Bullying is an escalating process where the victim experiences systematic negative social acts that lead to inferiority (Einarsen et al., 2003).

According to Rayner (1997), different types of bullying can be categorised as follows: threat to professional status (belittling opinion, public professional humiliation, accusation regarding lack of effort); threat to personal reputation (name-calling, insults, intimidation, devaluing); isolation (preventing growth opportunities, physical or social isolation, withholding information); overwork (undue pressure, impossible deadlines, unnecessary disruptions); and destabilisation (failure to give recognition, assigning of meaningless tasks, removal of responsibility, repeated reminders of blunders and setting the victim up to fail).

Namie and Namie (2003) suggested that 82% of employees who had been bullied left their workplaces, 38% for health reasons and 44% because they were victims of a low performance appraisal manipulated by a bullying superior to show them as incompetent. According to Watkins (2007),a person who experiences persistent intimidation might learn to expect bullying behaviour from others and develop a pattern of compliance with the unfair demands of those he or she perceives as stronger. Furthermore, Baillien et al. (2009) advised that future research should focus on the distinction between different perpetrators of bullying in the organisation, such as superiors and colleagues.

Workplace bullying

Superiors are perpetrators of workplace bullying in 60% – 80% of cases (Hoel & Cooper, 2000;Lutgen-Sandvik, Tracy & Alberts, 2007;Namie & Namie, 2003). Both Rayner and Keashly (2005) and Zapf and Einarsen (2005) ascertained that, with the exception of Scandinavian studies (Einarsen, 2000; Einarsen & Skogstad, 1996; Mikkelsen & Einarsen, 2002),most studies have consistently found superiors to be involved in 50% – 70% of all bullying cases (Cowie et al., 2000; Hoel, Cooper & Faragher, 2001). In a nationally representative survey (Namie, 2007), 72% of reported bullies were managers, some of whom had the sponsorship and support of executives, managerial peers, or human resource professionals. Thus, it can be assumed that superiors are more likely than colleagues to act as the perpetrators.

Hypothesis 1: Workplace bullying by superiors will be more prevalent in organisations than workplace bullying by colleagues.

Bullying behaviours also exist because of a ‘white wall of silence’, where the superior often defends the perpetrator (Murray, 2007). Consequently, the superior can be the bully or even be the second degree perpetrator in a bullying situation where he or she defends the bully. According to IOMA (July, 2008), witnesses to workplace bullying believed in 43% of cases that the perpetrator of bullying had the support of one or more senior managers when harassing a victim. Similarly, Longo and Sherman (2007) suggest that superiors manipulate behaviour and often protect the bully instead of the victims. As a result, reporting bullying behaviour is often an unsatisfactory solution, especially since superiors are more likely to be associated with being the ‘support from the organisation’.

According to Leymann (1990), bullying exists in organisations characterised by deficiencies in work design, leadership and negative social climates. It is argued that where managers avoid taking charge or involving themselves with work and stress or interpersonal conflicts and tensions, there is a breeding ground for bullies (Leymann, 1996). Consequently, it can be expected that those exposed to bullying will experience their immediate superior as an abusive and tyrannical leader.

Bullying by colleagues

While superiors are the most common perpetrators of workplace bullying (Garcia, Hue, Opdebeeck & Van Looy, 2002),bullying can involve co-workers ‘mobbing’ other co-workers (Einarsen et al., 2003; Zapf & Einarsen, 2005). In the Scandinavian studies, bullying from colleagues was more commonly reported than bullying from superiors (Einarsen, 2000; Einarsen & Skogstad, 1996; Mikkelsen & Einarsen, 2002). Studies have shown that bullying among colleagues has a higher ratio than bullying by superiors.

In approximately a third of incidents, victims identified their colleagues or peer groups as the perpetrators, although bullying by colleagues is also interlinked with bullying by superiors. Conflict might be the origin of aggressive behaviour between colleagues, and potentially escalates into bullying when the behaviour becomes deliberate and purposeful (Strandmark & Hallberg, 2007). New or younger employees in the organisation are considered to be particularly vulnerable, as are ethnic minorities, owing to a lack of knowledge regarding their rights and the regulations of the workplace (Westhuses, 2004). Intimidation and blame in the organisation creates mutually held fears about future job security among employees (Vaez, Ekberg & LaFlamme, 2004). Job insecurity creates a climate of rivalry when employees see their colleagues as potential rivals for jobs. This may cause feelings of competition and suspicion, factors that are known to be associated with workplace bullying (Bjorkqvist et al., 1994).

Manipulative and inappropriate behaviour from colleagues has led to one in five employees quitting their jobs, creating a substantial staff retention problem for employers. A further 23% of employed people have raised complaints of bullying in the workplace but in two out of three cases, issues remain unresolved or the complaints have failed to affect the bullying campaigns in any way (Mason, 2010).

Bullying and perceived organisational support

According to Rhoades and Eisenberger (2002), perceived organisational support (POS) is founded on the assumption that employees form opinions regarding the extent to which an organisation values their contributions and cares about their well-being; moreover, less workplace bullying has been reported in organisations with a supportive (accommodating, trustworthy and caring) climate (Baillien, Neyens & De Witte, 2004).

Dimensions of POS have been established as follows: role clarity (Eisenberger, Rhoades & Cameron, 1999;Zapf, Knorz & Kulla, 1996), job information (Schat & Kelloway, 2003), participation in decision-making (Allen, Shore & Griffeth, 2003), support from co-workers (Djurkovic, McCormick & Casimir, 2004), supervisory support (Settoon, Bennett & Liden, 1996), which leads to increased job satisfaction (Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli & Lynch, 1997), performance (Shanock & Eisenberger, 2006), commitment (Hochwarter, Kacmar, Perrewe & Johnson, 2003) and reduced turnover (Allen et al., 2003; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002).

Targets as well as observers of workplace bullying suffer from an ill-conditioned work environment (Sheehan, Ramsay & Patrick, 2000) and these ill-conditioned work environments with role conflict, a lack of participation in decision-making processes and a lack of support from superiors emancipate a bullying culture (Quine, 2001).

Role conflict or role ambiguity manifests in work environments where bullying exists. Einarsen, Raknes and Matthiesen (1994) highlight the fact that employees who are uncertain about their job expectations will experience a lack of support from the organisation. Moreover, targets of bullying rated the work environment more negatively, particularly with respect to the experience of role ambiguity (Vartia, 1996; Zapf, 1999). Therefore, role clarity can buffer the impact of workplace bullying through providing a sense of perceived support from the organisation. Furthermore, one the one hand, clear evidence indicates that negative acts by superiors and colleagues, such as imposing demeaning tasks, excessive monitoring, excessive criticism, withholding of information and exclusion thereof, represent workplace bullying (Lewis & Gunn, 2007). On the other hand, factors shown to buffer the manifestation of workplace bullying can be justified by supportive management structures

(Cummings & Worley, 1997), and worker involvement and participation in decision-making (Marchington, 1995). In addition, studies conducted in the UK and Scandinavia have shown that many employees from both public and private sector organisations are frequently subjected to physical and verbal abuse by their colleagues and/or superiors (Adams, 1992; Leymann, 1990; Randall, 1997; Wilson, 1991). A lack of social support from colleagues in the work environment places targets in a more vulnerable position and so they become an easier target for bullies (Sheehan et al., 2000).

The aforementioned information clearly demonstrates that without a supportive culture in the organisation, workplace bullying will lead, directly or indirectly, to targets in the organisation to have an increased intention to resign (Djurkovic et al., 2004; Keashly, 2001; Quine, 2001).

Hypothesis 2: A negative relationship exists between workplace bullying by superiors and perceived organisational support (role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships).

Hypothesis 3: A negative relationship exists between workplace bullying by colleagues and perceived organisational support (role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships).

Bullying and turnover intention

Workplace bullying has been found to be a significant predictor of turnover (Begley, 1998), which incurs substantial costs for the organisation (Waldman, Kelly, Arora & Smith, 2004).

Hypothesis 4: A positive relationship exists between workplace bullying by superiors and turnover intention.

Hypothesis 5:A positive relationship exists between workplace bullying by colleagues and turnover intention.

Workplace bullying has widespread negative effects on organisations because it affects not only the targets but also those who witness bullying behaviour. Because of employers’ costs associated with bullying, such as: productivity loss, costs regarding interventions by third parties, turnover, increased sick-leave, workers’ compensation and disability claims and legal liability - employers should logically be motivated to stop workplace bullying (Hoel & Einarsen, 2010).

Perceived organisational support and turnover intention

Researchers have focused significant attention on the concept of POS as a key predictor of turnover intention (Maertz, Griffeth, Campbell & Allen, 2007). Hui, Teo and Lee (2007),examined both turnover intention and POS and concluded that POS was negatively related to thoughts of leaving the organisation. Conversely, POS was also positively related to staying with the organisation. POS was negatively related to thoughts about quitting a job as a result of negative acts in the workplace. Similarly, Kinnunen, Feldt and Makikangas (2008) found that POS was negatively related to the likelihood of leaving an organisation and the frequency of thoughts about leaving the organisation.

Accordingly, ‘a social network and social support are valuable resources that not only enable individuals to cope with a wide variety of extant stressors but may also facilitate proactive coping efforts’ (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997, p. 421). In a longitudinal study of manufacturing workers, Moore, Grunberg and Greenberg (2004) found that greater role clarity was significantly associated with less turnover intention. Moreover, role clarity creates a sense of purpose for employees, leading to the retention of employees by the organisation (Sümer & Van Den Ven, 2008). In addition, a variety of abusive supervisory behaviours (Zellars, Tepper & Duffy, 2002) and a lack of participation in decision-making intentions (Allen et al., 2003) have been identified as situations where the only solution lies in targets quitting their jobs.

Thus, Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa (1986) argue that targets who perceive greater support from their employing organisation would be more likely to feel obligated to ‘repay’ the organisation (Shore & Wayne, 1993).

To this end, the goal of this study is to add to the research on the existence of workplace bullying in the South African context and how targets of bullying perceive support from the organisation where such a culture prevails. The impact of this phenomenon on turnover intention in organisations should create encouragement to generate transformation.

Hypothesis 6: A negative relationship exists between perceived organisational support (role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships) and turnover intention.

Hypothesis 7: Perceived organisational support (role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships) plays a moderating role in the relationship between workplace bullying (superiors and colleagues) and turnover intention.

The potential value-add of the study

Avoidance by employers and employees to acknowledge the problem of workplace bullying hinders the awareness of the detrimental effects of such bullying on the world of work. By understanding the impact of bullying, organisations might be stimulated to buffer workplace bullying with sufficient support, such as role clarity, sufficient job information, joint decision-making and support from both the supervisors and colleagues of the targets.

International research (Baillien et al., 2009; Einarsen et al., 2009; Lutgen-Sandvik & Sypher, 2009; Namie & Namie, 2009; Ortega et al., 2009) has established the significance of workplace bullying worldwide. Consequently, this phenomenon cannot be ignored in the South African context.South Africa is still in the exploration phase of how workplace bullying affects a diverse developing country(Pieterson, 2007; Wright, 2008). Hence, this study will not only contribute to a better understanding of workplace bullying trends in South Africa and its relationship with employee turnover intention, but will also provide for preventive measures to minimise the risk of bullying behaviour in South African workplaces.

Contemporary research is essential in determining the influence of workplace bullying on the intention to leave an organisation. However, greater emphasis on the effects of workplace bullying creates more awareness so that organisations and employees can counteract its occurrence. Thus, organisations can be alert and prepared to target workplace bullying through interventions, policies and, as this study will reveal, perceived organisational support, in order to counteract this issue.

What will follow

In the sections to follow the research approach, research participants, measuring instruments, research procedure and statistical analyses are discussed. The results of the study are presented, followed by a discussion of the results.

Research approach

This article follows a quantitative research approach with a cross-sectional field survey. This approach is conducted by means of questionnaires to measure workplace bullying, turnover intention and POS at a single point in time (Trochim & Donnelly, 2007).

Research method

Research participants

The sample group is represented by an availability sample of 13 911 participants gathered over a spectrum of nine provinces and five sectors. The first table presents the biographical characteristics of the participants.

|

TABLE 1: Characteristics of the participants.

|

The sample (N = 13 911) embodies a variety of sectors in the South African industry (academic, financial, government, manufacturing, mining and other), in which the mining industry is represented by 5197 (37.4% of the total sample) participants and the academic environment has the lowest representation, with 209 (1.5%) participants. Afrikaans-speaking (5486) and Xitsonga-speaking (5486) participants make up most of the sample group with 78.8%, while 81 isiNdebele participants (0.6%) make up the smallest proportion of the language category. There are almost twice as many men, with 9158 (65.8%) participants, as women. Married people, represented by 8826 (63.4%) participants, those with tertiary education, represented by 4183 (40%) participants, and 4180 (30%) participants between the ages of 30 and 40 years old, make up most of the sample in each category respectively, while 41 (0.3%) widowers, and 3 (0.0%) participants younger than 20 years old, make up the least of each

category respectively. In order from the least to the most participants per race group are: Coloured people, 212 (1.5%), Indian people, 236 (1.7%), Black people, 3659 (26.3%) and White people, 5128 (36.9%). Most participants, 6820 (49%), come from the Gauteng area while the Northern Cape, with 23 participants (0.2%), is least represented.

Measuring instruments

A biographical questionnaire was administered in order to document the socio-demographic differences of the participants. Characteristics on this questionnaire included gender, age, race, language, marital status, educational level, geographical distribution and industry.

The South African Employee Health and Wellness Survey (SAEHWS) was administered to gather the data. The SAEHWS is a self-report instrument based on the dual-process model of work-related well-being (Rothmann & Rothmann, 2006), developed by Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli (2001), and is rooted in the assumption that employees’ perceptions and experiences represent imperative information regarding the wellness climate in an organisation. The validity of the factor structures of the SAEHWS is equivalent for different ethnic groups and organisations and is therefore culturally sensitive with no bias against any cultural group (Rothmann & Rothmann, 2006).South African norms were also developed and Rothmann and Rothmann (2006) reported that the reliability of the SAEHWS was satisfactory, with a Chronbach’s Alpha coefficient above 0.70.

For the purpose of this study the following sections from the SAEHWS were used:

Workplace bullying was measured in terms of bullying by superiors and bullying by colleagues to determine the main culprits. The scale for workplace bullying by superiors consisted of a 1–4 (‘never’ to ‘always’) Likert scale range with 12 items asking questions such as: ‘How often do you experience unpleasant personal remarks from your superiors?’ (α = 0.87). The scale for workplace bullying by colleagues is also determined by a 1–4 Likert scale (‘never’ to ‘always’) where responses to 12 items can be evaluated, with questions such as: ‘How often do you feel that your colleagues are spreading unfair rumours about you?’ (α = 0.86).

To determine the role of POS in this study, it was measured, for the sake of accuracy, by utilising the sub-facets of the stated definition (role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships). Therefore, questions will be representative of each sub-facet. All sub-facets will be measured on a Likert scale 1–4 (‘never’ to ‘always’) range with three items, including questions relating to the various sub-facets, such as role clarity: ‘Do you know exactly what your responsibilities are?’ (α = 0.85); job information: ‘Do you receive sufficient information on the results of your work?’ (α = 0.82); participation in decision-making: ‘Can you participate in decisions about the nature of your work?’ (α = 0.82); colleague support: ‘If necessary, can you ask your colleagues for help?’ (α = 0.84)

and supervisory relationships: ‘Do you get on well with your direct supervisor?’ (α = 0.84).

To determine the cost to the company, turnover intention was explored. The turnover intention was rated on a 1–6 Likert scale (‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’) with five items, where questions like: ‘I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career in this organisation’ were asked (α = 0.86).

Research procedure

The data were gathered in collaboration with AfriForte over a period of three years from 2007 to 2010. The data were collected from all nine provinces and specified sectors. Participants were requested to follow a link received via e-mail and to complete the computerised questionnaire online. A letter of informed consent was completed by all participants and confidentiality was maintained throughout the research process.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out by means of the SPSS-programme (SPSS Inc., 2009). Descriptive statistics (e.g. means, standard deviations, skewness and kurtosis) were used to analyse the data. Cronbach Alpha coefficients were used to assess the internal consistency, homogeneity and unidimensionality of the measuring instruments (Clark & Watson, 1995). The Eigen values and screen plot were studied to determine the number of extracted factors. A principal components analysis with a direct Oblimin rotation was conducted in the case where factors were related (r > 0.30). A principal component analysis with a Varimax rotation was used if obtained factors were not related (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001).

To specify the relationship between the variables, Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were used in the case of normal distribution, and Spearman product-moment correlation coefficients for skew distributions. In terms of statistical significance, it was decided to set the value at a 95% confidence interval level (p ≤ 0.05). Effect sizes (Steyn, 1999) were used to decide on the practical significance of the findings. The practical significance of correlation coefficients was set with a medium effect (p ≥ 0.30) and a large effect (p ≥ 0.50).

Logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the proportion of variance in the dependent variable (turnover intention) that is predicted by the independent variable (workplace bullying). A hierarchical regression analysis, as recommended by Aiken and West (1991), was performed in order to determine the moderating effect of the moderator variable (POS) on the relationship between the independent variable (workplace bullying) and the dependent variable (turnover intention). To provide a clearly interpretable interaction term and to reduce multicollinearity, the variables were standardised. In Step 1, the independent variable (workplace bullying) was regressed with the dependent variable (turnover intention). In the following steps, the dimensions of the moderator variable (POS, i.e. role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationship) were entered. The order of entering these variables depended on the strength of the

correlations between the dimensions of the moderator variable (perceived organisational support) and the dependent variable (turnover intention). In the final step, the interaction term (workplace bullying × moderator) was added, and a moderating effect was confirmed if the interaction term was statistically significant and if explained variance (R2) was significantly increased (p < 0.05).

Descriptive statistics, internal consistencies and correlations

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics, internal consistencies (Cronbach alpha coefficients) and correlations between workplace bullying, POS (role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships) and turnover intention.

|

TABLE 2: Descriptive statistics, Cronbach alpha coefficients and correlation coefficients of the SAEHWS.

|

Table 2 represents the satisfactory Cronbach alpha coefficients obtained for all the scales which were higher than the guideline of a > 0.70 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). All the items are normally distributed except for bullying by superiors and colleagues, role clarity and job information. Therefore, for these constructs the Spearman product-moment correlations will apply. Pearson product-moment correlations were used for all the other scales.

Table 3 indicates that bullying by superiors shows a positive statistically and practically significant correlation (with a large effect) with bullying by colleagues, and a negative statistically and practically significant correlation (with a large effect) with supervisory relationships. Also, negative statistically and practically significant correlations were found (with a medium effect) between bullying by superiors and work role clarity, job information and participation in decision-making. A positive statistically significant correlation was found between bullying by superiors and turnover intention.

|

TABLE 3: Correlation coefficients between workplace bullying (superiors and colleagues), POS and turnover intention.

|

Bullying by colleagues is negatively correlated with all constructs with a statistically significant relationship; however, practically significant correlations with a medium effect were found with colleague support and supervisory relationships. A positive statistically significant correlation was found between bullying by colleagues and turnover intention.

|

TABLE 4: Hierarchical regression analysis (role clarity) with turnover intention as dependent variable.

|

Role clarity shows a positive statistical significance with all constructs and a practical significance (with a large effect) with job information, supervisory relationships and participation in decision-making. A practical significance (with a medium effect) was found between role clarity and colleague support, whereas a negative practically significant correlation was shown for turnover intention. Job information shows a positive statistically and practically significant correlation with all constructs: supervisory relationships and participation in decision-making (large effect) and colleague support, and a negative statistically and practically significant correlation with turnover intention (medium effect).

|

TABLE 5: Hierarchical regression analysis (participation in decision-making) with turnover intention as dependent variable.

|

To address the last objective of this research study, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted in order to determine if POS acts as a moderator in the relationship between workplace bullying (either by superiors or by colleagues) and turnover intention.

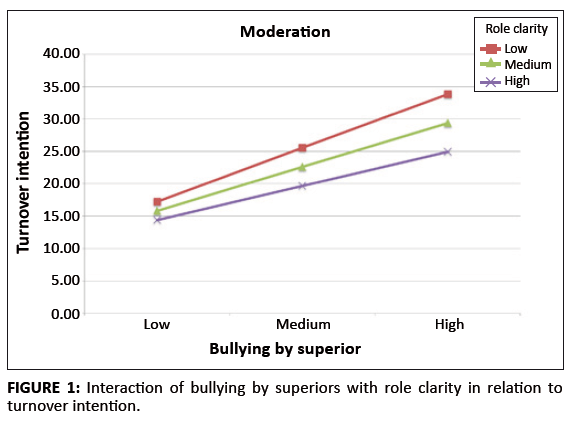

In step one of the hierarchical regression, role clarity was regressed on turnover intention (β = -0.32, p = 0.00) producing a significant model. The entering of bullying by superiors in step two produced a significant model (β = 0.18, p = 0.00). In the third step the interaction term was entered, producing a significant model (β = 0.03, p = 0.00). Thus, role clarity, as one of the defined sub-facets of POS, proves to play a significant role in the relationship between workplace bullying by superiors and the tendency to leave the organisation. A target who has clarity on his or her role might consider staying in the organisation, despite workplace bullying which would usually be serious enough to lead to resignation.

|

TABLE 6: Hierarchical regression analysis (supervisory relationship) with turnover intention as dependent variable.

|

Figure 1 shows that when bullying by superiors manifests, targets who perceive less support from their organisations (in experiencing role ambiguity) have a much higher tendency to leave the organisation. However, it can also be seen that when targets’ experience of role clarity increases, those targets being bullied by their superiors will, in comparison with those employees who experience low levels of support, be more inclined to stay in the organisations despite the bullying culture.

|

FIGURE 1: Interaction of bullying by superiors with role clarity in relation to

turnover intention.

|

|

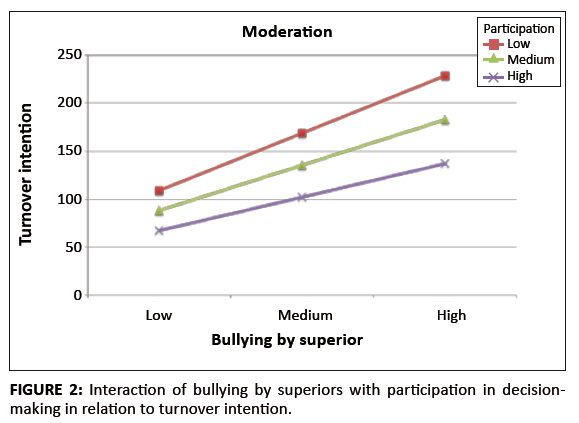

In step one of the hierarchical regression, participation in decision-making was entered and a significant model was produced (β = -0.37, p = 0.00). Bullying by superiors was entered in step two which produced a significant model (β = 0.14, p = 0.00). In the third step the interaction term was entered, producing a significant model (β = 0.03, p = 0.00). This indicates that participation in decision-making, as one of the defined sub-facets of POS, plays a significant role in the relationship between workplace bullying by superiors and the tendency to leave the organisation. If the targets of bullying by superiors feel that they can participate in the decision-making processes of the organisation, this indicates that their perceived support from the organisation is intact. When these targets are bullied by their superiors, having perceived support in the form of participation means that they do not leave the organisation, despite being bullied. On the other hand,

when experiencing bullying from a superior while also not being informed or included in the decision-making processes, the target’s final counteraction towards the bullying culture will be to leave the organisation.

Figure 2 shows that when targets of bullying by superiors experience POS through participation in decision-making, their tendency to leave the organisation will be minimised. However, it can also be seen that when targets experience exclusion from decision-making processes together with being bullied by their superiors, they will be more inclined to leave the organisation because of a lack of support from the organisation.

|

FIGURE 2: Interaction of bullying by superiors with participation in decisionmaking

in relation to turnover intention.

|

|

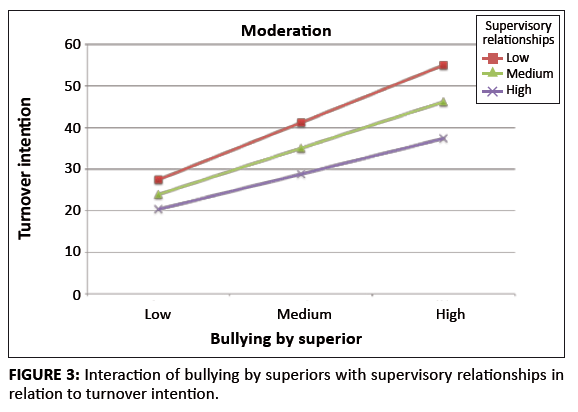

Supervisory relationship was entered in step one of the hierarchical regression and a significant model was produced (β = -0.32, p = 0.00). Bullying by superiors was entered in step two which produced a significant model (β = 0.14, p = 0.00). In the third step the interaction term was entered, producing a significant model (β = 0.06, p = 0.00). This implies that relationships with a superior play a significant role in the relationship between bullying by superiors and turnover intention. When the targets experience healthy relationships with their superiors they will feel supported by their superiors and, therefore, by the organisation. When bullying by superiors manifests but the perceived support through supervisory relationships exists, the targets of the bullying phenomenon will not be inclined to leave the organisation. However, when the employees have poor working relationships with their superiors while also experiencing bullying from them, the targets will

be much more driven to resign than to fight an overwhelming battle.

Figure 3 indicates that when employees have insufficient support from their organisations due to unhealthy relationships with their superiors, workplace bullying by superiors can easily emerge. Conversely, when employees’ POS exists with the focus on healthy relationships with their superiors, being bullied by their superiors will not be enough to drive the targets of bullying by superiors to find their solution in absenteeism leading to resignation.

|

FIGURE 3: Interaction of bullying by superiors with supervisory relationships in

relation to turnover intention.

|

|

The aforementioned hierarchical regression analysis reveals that when employees are bullied by superiors, role clarity, participation in decision-making and supervisory relationships (sub-facets of POS) will moderate the relationship between superior bullying and turnover intention. There seem to be no moderating relationships when being bullied by colleagues.

The main purpose of this study was to explore bullying (by superiors and colleagues), perceived support by employees in the organisation and the influence of workplace bullying on the turnover intention. Therefore, POS (role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships) was investigated as a possible moderator in the relationship between workplace bullying, either by superiors or colleagues, and the intention to leave the organisation. As mentioned in the literature review, little research has been done in the South African context concerning the perpetrators of bullying, the relationship between workplace bullying and turnover intention, and the buffering effect of POS on this relationship.

The internal consistency reported that all the constructs were reliable, with a coefficient above 0.7. The reliability coefficients varied between 0.82 and 0.87. All the items were normally distributed except for bullying by superiors and colleagues, role clarity and job information. Consequently, the Spearman product-moment correlations were utilised. Pearson product-moment correlations were used for all the other scales as their distributions were normally distributed. These correlations reported on the type of the relationship and the effect sizes between the variables.

When interpreting the results, the first hypothesis, that bullying by superiors is more prevalent than bullying by colleagues, can be confirmed. This has previously been substantiated by the research of Hoel and Cooper (2000),Lutgen-Sandvik et al. (2007) andNamie and Namie (2003). Bullying by superiors has a greater influence than bullying by colleagues on the targets leaving the organisation.

The significance of the correlations confirmed hypotheses three and four, namely that workplace bullying by superiors or colleagues has negative relationships with all the sub-facets of POS (role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships). This implies that when bullying increases, POS will decrease. These findings are consistent with recent studies suggesting that the employees affected by bullying in the workplace experience a lack of role clarity (Agervold, 2007; Hauge, Skogstad & Einarsen, 2010), important information will be kept from them on purpose (Johnson & Rea, 2009), they will have less control over decisions being made in the organisation (Notelaers, De Witte & Einarsen, 2010; Quine, 2001), they will experience less support from colleagues and supervisors (Notelaers & De Witte, 2003; Tsuno, Kawakami, Inoue & Abe, 2010). Supervisory relationships correlated with a large effect in comparison with the

other sub-facets, which indicates the prevalence of poor supervisory relationships in a bullying culture as found in previous research.

Both bullying by superiors and bullying by colleagues correlated positively with turnover intention (providing support for hypotheses four and five), indicating that when the bullying by either superiors or colleagues increases, the target’s intention to leave the organisation will also increase. This confirms the results of several previous studies that bullying icreases an individual’s intention to leave the organisation (i.e. Berthelsen, Skogstad, Lau & Einarsen, 2011; Djurkovic et al., 2004; Hoel & Cooper, 2000). Bullying by superiors had a slightly higher correlation with turnover intention than bullying by colleagues, indicating that the influence of bullying by superiors on the intention to leave the organisation is greater than the influence of bullying by colleagues.

The POS in the organisation established its significance in the relationship with turnover intention, with a negative association, confirming hypothesis six. This implies that in the presence of the sub-facets of POS (role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships) the turnover intention in the organisation will decrease, leading to targets not considering leaving the organisation. This result confirms the results of previous studies suggesting that turnover intention is influenced by the extent to which employees experience role clarity (Bhuian, Menguc & Borsboom, 2005; Hwang & Chang, 2009), have sufficient job information (Lambert, 2006), participate in the decision-making process (Knudsen, Ducharme & Roman, 2009), and are supported by their colleagues (Brough & Frame, 2004; Kim & Stoner, 2008) and supervisor (Lambert, 2006; Maertz et al., 2007).

Hypothesis seven stated that POS (role clarity, job information, participation in decision-making, colleague support and supervisory relationships) plays a moderating role in the relationship between workplace bullying and turnover intention. This hypothesis is partially confirmed. According to the results, POS (role clarity, participation in decision-making and supervisory relationships) acted as moderator in the relationship between workplace bullying by superiors and turnover intention. However, the results indicate that the POS variables job information and colleague support did not moderate the relationship between workplace bullying and turnover intention. Similarly, no moderation was found with bullying by colleagues. A study by Djurkovic et al. (2004) yielded similar findings of the moderating role of POS in the relationship between bullying and turnover intention, however, in this study the definition used to define POS differed slightly from the definition used in this study.

As a result, when superiors bully their subordinates and the targets have a clear understanding of what their roles in the organisation are, these victims will be more inclined to consider not leaving the organisation. Similarly, when they have a say in the decisions of the organisation the targets will also remain. Furthermore, when employees are bullied by superiors, but have excellent relationships with other superiors, then this will also counteract the effects of workplace bullying on the intention to leave the organisation. There were no sub-facets of POS acting as moderators in the relationship between bullying by colleagues and turnover intention.

To conclude, the primary objective of this study was to determine whether POS moderates the relationship between workplace bullying and turnover intention. The results of this study confirm this moderating effect, suggesting that when bullied by supervisors, a lack of POS (more specifically role clarity, participation in decision-making and supportive supervisory relationships) will increase bullying victims’ propensity to leave the organisation. This intensifies the need for organisations to provide a supportive environment for their employees, especially those being targeted by bullies.

Limitations in this study could be addressed in future research. The first limitation is that longitudinal research can compile more profound evidence of what is being researched, which was not the case with this research study. Another limitation is that this study focused on many sectors, which makes the counteraction strategies less specific to any particular sector. A further setback was that there was no satisfactory evidence to prove that POS can act as a moderator in the case of bullying by colleagues, and this could still be an important element in South African research.

The findings of this research lay the foundation for further research with regard to workplace bullying in the South African context. Whereas this study gave a broad overview of the manifestation of workplace bullying in many sectors in South Africa, more in-depth research is necessary in order to provide a framework for the development of preventative interventions or support programmes for those individuals targeted with bullying. Longitudinal studies would allow researchers to draw accurate conclusions regarding the development of turnover intentions of individuals being bullied at work. Also, more information is needed regarding other organisational factors predicted by bullying in the workplace if a comprehensive model of workplace bullying is to be developed. Workplace bullying is a silent epidemic (McAvoy & Murtagh, 2003) and will remain so if no counteraction is encouraged through research and implemented in practice.

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Afriforte (Pty) Ltd. for the use of their data and the assistance with the statistical analyses.

Authors’ contributions

C.E. was the project leader of the study, and L.v.S. and C.E. were responsible for the conceptual contributions. L.v.S. and C.E. wrote the manuscript of which L.v.S. made the largest contribution. I.R. was responsible for the project design and conducted the statistical analyses, which were interpreted by L.v.S. and C.E.

Adams, A. (1992). Bullying at work: How to confront and overcome it. London, UK: Virago.

Agervold, N. (2007). Bullying at work: A discussion of definitions and prevalence, based on an empirical study. Scandinavia Journal of Psychology, 48(2),

161–172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00585.x,

PMid:17430369

Aiken, L.S., & West S.G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Allen, D.G., Shore, L.M., & Griffeth, R.W. (2003). The role of perceived organizational support and supportive human resource practices in the

turnover process. Journal of Management, 29(1), 99–118.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014920630302900107

Aspinwall, L., & Taylor, S. (1997). A stitch in time: Self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 417–436.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.417,

PMid:9136643

Baillien, E., Neyens, I., & De Witte, H. (2004). Literature review on physical violence, bullying and sexual harassment at work: The influence of

organizational, team-related and task-related characteristics. Leuven, Belgium: KU Leuven Department of Psychology.

Baillien, E., Neyens, I., De Witte, H., & De Cuyper, N. (2009). A qualitative study on the development of workplace bullying: Towards a three way model.

Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 19(1), 1–16.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/casp.977

Baron, R.A., & Neuman, J.H. (1998). Workplace aggression - the iceberg beneath the tip of workplace violence: evidence on its forms, frequency and targets.

Public Administration Quarterly, 21(4), 446–464.

Bassman, E.S. (1992). Abuse in the workplace: Management remedies and bottom line impact. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Begley, T. (1998). Coping strategies as predictors of employee distress and turnover after an organizational consolidation: A longitudinal analysis. Journal

of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 71(4), 305–329.

Berthelsen, M., Skogstad, A., Lau, B., & Einarsen, S. (2011). Do they stay or do they go?: A longitudinal study of in and exclusion from working life among

targets of work. International Journal of Manpower, 32(2), 1.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01437721111130198

Bhuian, S.N., Menguc, B., & Borsboom, R. (2005). Stressors and job outcomes in sales: A triphasic model versus a linear-quadratic-interactive model.

Journal of Business Research, 58(2), 141–150.

Bilgel, N., Aytac, S., & Bayram, N. (2006). Bullying in turkish white-collar workers. Occupational Medicine, 56(4), 226–231.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqj041,

PMid:16507600

Björkvist, K., Österman, K., & Hjelt-Bäck, M. (1994). Aggression among university employees. Aggressive Behavior, 20(3), 173–184.

Bloisi, W., & Hoel, H. (2008). Abusive work practices and bullying among chefs: a review of the literature. International Journal of Hospitality

Management, 27(4), 649–656. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2007.09.001

Brough, P., & Frame, R. (2004). Predicting police job satisfaction and turnover intentions: The role of social support and police organisational variables.

New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 33, 8–16.

Clark, L.A., & Watson, D. (1995). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 309–319.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309

Cowie, H., Jennifer, D., Neto, C., Angulo, J.C., Pereira, B., Del Barrio, C. et al. (2000). Comparing the nature of workplace bullying in two European

countries: Portugal and the UK. In M. Sheehan, S. Ramsay & J. Patrick (Ed.), Transcending boundaries: Integrating people, processes and systems, conference

proceedings, (pp. 120–125). Brisbane, Queensland: Griffith University.

Cummings, T., & Worley, C. (1997). Performance management, in organization development and change. OH: South-Western College Publishing.

Davenport, N., Schwartz, R., & Elliott, G. (1999). Mobbing: Emotional abuse in the American workplace. Ames, Iowa: Civil Society Publishing.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A.B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3),

499–512.

Djurkovic, N., McCormick, D., & Casimir, G. (2004). The physical and psychological effects of workplace bullying on intention to leave: A test of the

psychosomatic and disability hypotheses. International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior, 7(4), 469–497.

Duffy, M., & Sperry, L. (2007). Workplace mobbing: Individual and family health consequences. The Family Journal, 15(4), 398–404.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1066480707305069

Einarsen, S. (2000). Harassment and bullying at work: A review of the Scandinavian approach. Aggressive Violent Behaviour, 5(4), 379–401.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(98)00043-3

Einarsen, S., & Skogstad, A. (1996). Bullying at work: Epidemiological findings in public and private organizations. European Journal of Work and

Organisational Psychology, 5, 185–201.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414854

Einarsen, S., Aasland, M., & Skogstad, A. (2007). Destructive leadership behaviour: A definition and conceptual model. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3),

207–216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.002

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Notelaers, G. (2009). Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: validity factor structure and psychometric properties

of the negative acts questionnaire-revised. Work and Stress, 23(1), 24–44.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02678370902815673

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (2003). Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace: International perspectives in research and

practice. London, UK: Taylor & Francis.

Einarsen, S., Raknes, B.I., & Matthiesen, S.B. (1994). Bullying and harassment at work and their relationships to work environment quality: An exploratory

study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 4(4), 381–401.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13594329408410497

Eisenberger, R., Cummings, J., Armeli, S., & Lynch, P. (1997). Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment and job satisfaction. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 75(1), 51–59.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3),

500–507.

Eisenberger, R., Rhoades, L., & Cameron, J. (1999). Does pay for performance increase or decrease perceived self-determination and intrinsic motivation?

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(5), 1026–1040.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1026

Garcia, A., Hue, C., Opdebeeck, S., & Van Looy, J. (2002). Geweld op het werk, pesterijen en ongewenst seksueel gedrag: eigenschappen en gevolgen voor de

mannelijke en vrouwelijke werknemers [Violence, bullying and sexual harassment at work: characteristics and consequences for male and female employees]. Louvain

La Neuve: Universite Catholique de Louvain.

Hauge, L.J., Skogstad, A., & Einarsen, S. (2010). The relative impact of workplace bullying as a social stressor at work. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology,

51(5), 426–433.

Hochwarter, W.A., Kacmar, C., Perrewe, P.L., & Johnson, D. (2003). Perceived organizational support as a mediator of the relationship between politics perceptions

and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 438–456.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00048-9

Hoel, H., & Cooper, C.L. (2000). Destructive conflict and bullying at work. Unpublished report. Manchester, United Kingdom: Manchester School of

Management, University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology.

Hoel, H., & Einarsen, S. (2010). Shortcomings of anti-bullying regulations: The case of Sweden. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology,

16(2), 101–118.

Hoel, H., Cooper, C.L., & Faragher, B. (2001). The experience of bullying in Great Britain: The impact of organizational status. European Journal of Work

and Organizational Psychology, 10(4), 443–465.

Holt, S. (2004, 20 December). Bullying at work gains visibility. Seattle Times, p. 1.

Hui, K.L., Teo, H.H., & Lee, S.Y.T. (2007). The Value of privacy assurance: An exploratory field experiment. MIS Quarterly, 31(1), 19–33.

Hwang, J.I., & Chang, H. (2009). Work climate perception and turnover intention among Korean hospital staff. International Nursing Review, 56(1),

73–80.

Institute of Management & Administration (IOMA). (2008). Productivity drain from bullying demands new look. Business intelligence at work,

8(7), 13. Retrieved April 25, 2010, from http://www.ioma.com/secure

Johnson, S.L., & Rea, R.E. (2009). Workplace bulling: Concerns for nurse leaders. Journal of Nursing Administration, 39(2), 84–90.

Keashly, L. (2001). Interpersonal and systemic aspects of emotional abuse at work: the target’s perspective. Violence and Victims, 16(3),

233–68.

Kim, H., & Stoner, M. (2008). Burnout and turnover intention among social workers: Effects of role stress, job autonomy and social support. Journal of

Administration in Social Work, 32(3), 5–25.

Kinnunen, U., Feldt, T., & Makikangas, A. (2008). Testing the effort-reward balance among Finnish managers: the role of perceived organizational support.

Journal of Occupational Health, 13(2), 114–127.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.13.2.114,

PMid:18393581

Knudsen, H.K., Ducharme, L.J., & Roman, P.M. (2009). Turnover intention and emotional exhaustion ”at the top”: Adapting the Job Demands-Ressources

Model to leaders of addiction treatment organizations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(1), 84–95.

Koonin, M., & Green, T.M. (2004). The emotionally abusive workplace. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 4(3/4), 71–79.

Lambert, E.G. (2006). I want to leave: A test of a model of turnover intent among correctional staff. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice, 2(1),

57–83.

Lewis, D., & Gunn, R. (2007). Workplace bullying in the public sector: understanding the racial dimension. Journal Compilation, 85(3), 641–665.

Lewis, D., & Sheehan, M. (2003). Workplace bullying: Theoretical and practical approaches to a management challenge. International Journal of Management

and Decision Making, 4(1), 1–10.

Lewis, J., Coursol, D., & Wahl, K.H. (2002). Addressing issues of workplace harassment: Counseling the targets. Journal of Employment Counseling, 39,

109–116.

Lewis, S., & Orford, J. (2005). Women’s experiences of workplace bullying: Changes in social relationships. Journal of Community & Applied

Social Psychology, 15(1), 29–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/casp.807

Leymann, H. (1990). Mobbing and psychological terror at workplaces. Violence and Victims, 5(1), 119–126.

Leymann, H. (1996). The content of development of mobbing at work. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 5(2), 165–184.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414853

Leymann, H., & Gustafsson, A. (1996). Mobbing at work and the development of post-traumatic stress disorders. European Journal of Work and Organizational

Psychology, 5(2), 251–275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414858

Longo, J., & Sherman, R.O. (2007). Leveling horizontal violence. Nursing Management, 38(3), 34–51.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.NUMA.0000262925.77680.e0

Lutgen-Sandvik, P., & Sypher, B.D. (2009). Destructive organizational communication. New York: Routledge Press.

Lutgen-Sandvik, P., Tracy, S.J., & Alberts, J.K. (2007). Burned by bullying in the American workplace: Prevalence, perception, degree, and impact.

Journal of Management Studies, 44(6), 837–862. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00715.x

MacIntosh, J. (2005). Experiences of workplace bullying in a rural area. Issues in the Mental Health Nursing, 26(9), 893–910.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01612840500248189,

PMid:16203644

Maertz, C.P. Jr., Griffeth, R.W., Campbell, N.S., & Allen, D.G. (2007). The effects of perceived organizational support and perceived supervisor support on

employee turnover. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28(8), 1059–1075.

Marchington, M. (1995). Involvement and Participation. In J. Storey (Ed.), Human Resource Management: A critical Text, (pp. 328–351). Canada, USA:

Routledge.

Martin, A., & Jones, E. (2000). Sources of stress and strategies for intervention during organisational change in a hospital environment. In M.

Sheehan, S. Ramsay & J. Patrick (Eds.), Transcending boundaries: Integrating people, processes and systems, conference proceedings, (pp. 261–266).

Brisbane, Queensland: Griffith University.

Mason, L. (2010, February). Colleagues are the main culprits of workplace bullying. Mason Media, pp. 1–2.

Mathisen, G., Einarsen, S., & Mykletun, R. (2008). The occurrences and correlates of bullying and harassment in the restaurant sector. Scandinavian

Journal of Psychology, 49(1), 59–68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00602.x,

PMid:18190403

Matthiesen, S.B., Aasen, E., Holst, G., Wie, K., & Einarsen, S. (2003). The escalation of conflict: A case study of bullying at work. International

Journal of Management and Decision Making, 4(1), 96–112.

McAvoy, B., & Murtogh, J. (2003). Workplace bullying. British Medical Journal, 326(7393), 776–778.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7393.776,

PMid:12689952,

PMid:1125699

McCormick, D., Casimir, G., Djurkovic, N., & Yang, L. (2006). The concurrent effects of workplace bullying, satisfaction with supervisor, and satisfaction

with coworkers on affective commitment among schoolteachers in china. International Journal of Conflict Management, 17(4), 316–331.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10444060610749473

Mikkelsen, E.G., & Einarsen, S. (2002). Basic assumptions and symptoms of post-traumatic stress among victims of bullying at work. European Journal of

Work and Organizational Psychology, 11, 87–111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13594320143000861

Moore, S., Grunberg, L., & Greenberg, E. (2004). Repeated downsizing contact: The effects of similar and dissimilar layoff experiences on work and well-being

outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9(3), 247–257.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.9.3.247,

PMid:15279519

Moss, P.H., & Tilly, C. (2001). Stories employers tell. Race, skill, and hiring in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Murray, J.S. (2007). Before blowing the whistle, learn to protect yourself. American Nurse Today, 2(3), 40–42.

Namie, G. (2000). Quick view fact sheet. Retrieved January 08, 2011, from

http://bullyinginstitute.org/res/surv2000qv.html

Namie, G. (2007). The Workplace Bullying Institute 2007 U.S. Workplace Bullying Survey. Retrieved September 16, 2010, from

http://bullyinginstitute.org/wbi-zogby2.html

Namie, G., & Namie, R. (2003). The bully at work: What you can do to stop the hurt and reclaim your dignity on the job. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks.

Namie, G., & Namie, R. (2009). U.S. workplace bullying: Some basic considerations and consultation interventions. Consulting Psychology Journal:

Practice and Research, 61(3), 202–219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0016670

Notelaers, G., & De Witte, H. (2003). Pesten op het werk: Omvang en welke gedragingen? [Bullying at work: prevalence and types of behaviours?]. Over

Werk, 13, 165–169.

Notelaers, G., De Witte, H., & Einarsen, S. (2010). A job characteristics approach to explain workplace bullying. European Journal of Work and

Organisational Psychology, 19(4), 487–504.

Nunnally, J.C., & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric theory. (3rd edn.). New York: McGraw- Hill.

Ortega, A., Høgh, A., Pejtersen, J. H., & Olsen, O. (2009). Prevalence of workplace bullying and risk groups: a representative population study.

International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 82(3), 417–426.

Pager, D., & Quillian, L. (2005). Walking the talk? What employers say versus what they do. American Sociological Review, 70(3), 355–380.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000312240507000301

Pietersen, C. (2007). Interpersonal bullying behaviours in the workplace. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology/SA Tydskrif vir Bedryfsielkunde, 33(1),

59–66.

Quine, L. (1999). Workplace bullying in NHS community trust: Staff questionnaire survey. British Medical Journal, 318(7178), 228–232.

Quine, L. (2001). Workplace bullying in nurses. Journal of Health Psychology, 6(1), 73–84

Randall, P. (1997). Adult bullying: Perpetrators and victims. London: Routledge.

Rayner, C. (1997). The incidence of workplace bullying. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 7(3), 199–208.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1298(199706)7:3<199::AID-CASP418>3.0.CO;2-H

Rayner, C. (1999). From research to implementation: Finding leverage for prevention. International Journal of Manpower, 20(1), 28–38.

Rayner, C., & Keashly, L. (2005). Bullying at work: A perspective from Britain and North America. In S. Fox & P.E. Spector (Eds.),

Counterproductive behaviour: Investigations of actors and targets, (pp. 271–296). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10893-011

Rayner, C., Hoel, H., & Cooper, C.L. (2002). Workplace bullying: What we know, who is to blame, and what can we do? London, UK: Taylor & Francis.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714.

Roscigno, V., Garcia, L., & Bobbitt-Zeher, D. (2007). Social closure and process of race/sex employment discrimination. Annals of the American Academy of

Political and Social Science 609(1), 16–48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002716206294898

Rothmann, J.C., & Rothmann, S. (2006). The South African Employee Health and Wellness Survey: User manual. Potchefstroom, South Africa: Afriforte

(Pty) Ltd.

Schat, A.C.H., & Kelloway, E.K. (2003). Reducing the adverse consequences of workplace aggression and violence: The buffering effects of organizational

support. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8(20), 110–122.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.8.2.110,

PMid:12703877

Settoon, R.P., Bennett, N., & Liden, R.C. (1996). Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader-member exchange, and employee

reciprocity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(3), 219–227.

Shanock, L.R., & Eisenberger, R. (2006). When supervisors feel supported: Relationships with subordinates’ perceived supervisor support, perceived

organizational support, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(3), 689–695.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.689,

PMid:16737364

Sheehan, M. (1999). Workplace bullying: Responding with some emotional intelligence. International Journal of Manpower, 20(1/2), 57–69.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01437729910268641

Sheehan, M., Ramsay, S., & Patrick, P. (2000). Transcending boundaries: Integrating people, processes and systems. Australia: The School of

Management, Griffith University.

Shore, L.M., & Wayne, S.J. (1993). Commitment and employee behavior: A comparison of affective commitment and continuance commitment with perceived

organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(5), 774–780.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.5.774,

PMid:8253631

Sperry, L. (2009). Workplace mobbing and bullying: A consulting psychology perspective and overview. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research,

61(3), 165–168.

SPSS Inc, S. (2009). SPSS 16.0 for Windows. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc.

Steyn, H.S. (1999). Praktiese betekenisvolheid: Die gebruik van effekgroottes [Practical significance: The use of effect sizes]. Wetenskaplike

bydraes – Reeks B: Natuurwetenskappe Nr. 17. Potchefstroom: PU vir CHO.

Strandmark, M., & Hallberg, L.R.M. (2007). The origin of workplace bullying: Experiences from the perspective of bully victims in the public service sector.

Journal of Nursing Management, 15(3), 332–341.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00662.x,

PMid:17359433

Sümer, H., & Van Den Ven, C. (2008). A proposed model of military turnover. Technical Report. NATO Research and Technology Organization

(Reference Number: RTO-TR-HFM- 107).

Tabachnick, B., & Fidell, L. (2001). Using multivariate statistics. (4th edn.). New York: HarperCollins College Publishers.

Trochim, W., & Donnelly, J.P. (2007). The research methods knowledge base. (3rd edn.). Mason, OH: Thomson Learning.

Tsuno, K., Kawakami, N., Inoue, A., & Abe, K. (2010). Measuring workplace bullying: Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Negative Acts

Questionnaire. Journal of Occupational Health, 52, 216–226.

Vaez, M., Ekberg, K., & LaFlamme, L. (2004). Abusive events at work among young working adults. Relations Industries, 59(3), 569–584.

Vartia, M. (1996). The sources of bullying - psychological work environment and organizational climate. European Journal of Work and Organizational

Psychology, 5(2), 203–214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414855

Waldman, J.D., Kelly, F., Arora, S., & Smith, H.L. (2004). The shocking cost of turnover in health care. Health Care Management Review, 29(1), 2–7.

Watkins, C.E. (2007). Protecting against bullies: Throughout the life cycle. Northern County Psychiatric Association. Retrieved May 09, 2010, from

http://www.ncpamd.com/Bullying_Thru_Life_Cycle.htm

Westhuses, E. (2004). Work place mobbing in academe. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

Wilson, C.B. (1991). U.S. businesses suffer from workplace trauma. Personnel Journal, 70(7), 47–50.

Wilson, M. (1997). Reward Systems. In P. Boxall (Ed.), The challenge of human resource management, (pp. 135–156). New Zealand, Auckland:

Longman Paul.

Wood III, J.D. (2008). Bullying cognitions through identification with fictional characters. Newberg, OR: George Fox University.

Wornham, D.A. (2003). Descriptive investigation of morality and victimisation at work. Journal of Business Ethics, 45, 29–40.

Wright, A. (2008, June 12). Abusive behavior is workers’ top ethical concern. HRNews. Retrieved on June 11, 2010, from

http://www.shrm.org/hrnews_published/articles/CMS_025812.asp#P-8_0

Zapf, D. (1999). Organizational, work group related and personal causes of mobbing/bullying at work. International Journal of Manpower, 20(1/2), 70–85.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01437729910268669

Zapf, D., & Einarsen, S. (2001). Bullying in the workplace: Recent trends in research and practice – An introduction. European Journal of Work and

Organizational Psychology, 10(4), 369–373.

Zapf, D., & Einarsen, S. (2005). Mobbing at work: Escalated conflicts in organizations. In S. Fox & P.E. Spector (Eds.), Counterproductive work behavior.

Investigations of actors and targets, (pp. 237–270). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Zapf, D., Knorz, C., & Kulla, M. (1996). On the relationship between mobbing factors, and job content, social work environment, and health outcomes. European

Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 215–237.

Zellers, K., Tepper, B., & Duffy, M. (2002). Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology,

87(6), 1068−1076.

|